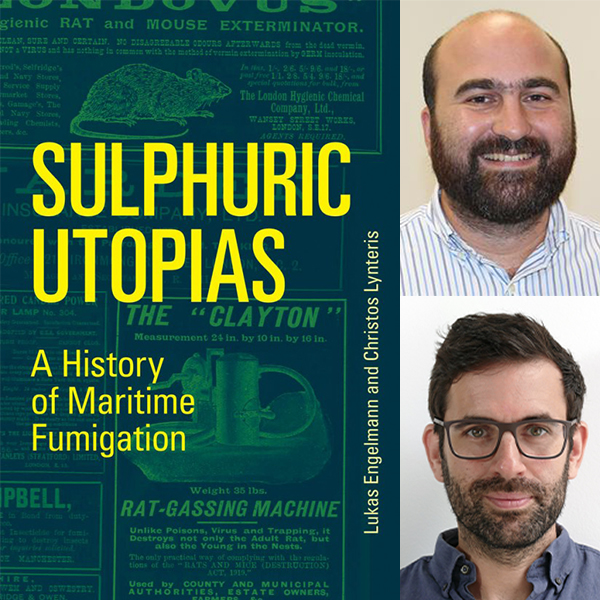

Christos Lynteris is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social Anthropology at St Andrew’s University. From 2011 – 2013 he was a CRASSH Mellon/Newton postdoctoral fellow and from 2013 – 2018 he was PI of The Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic ERC StG project at CRASSH.

Lukas Engelmann was a Post-doctoral Research Associate at Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic from 2014 – 2017 and is now a Chancellor’s Fellow / Senior Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh.

Q. Christos and Lukas, what is your book Sulphuric Utopias about?

Our book tells the story of a technology that transformed global practices of maritime quarantine at the end of the 19th century. Fumigation combined chemical and industrial engineering to apply gases like sulphur dioxide (SO2) to the task of eliminating pathogens, insects, and rats while leaving goods and the structure of the vessel itself unharmed. The purpose of fumigation at the time was to dramatically shorten detention times of ships and their cargo in quarantine stations. Using gas engineers and medical officers sought to minimise the risk of importing infectious diseases, such as yellow fever and plague, and to establish universally applicable standards of hygiene in maritime trade.

The book unpacks this story around a machine, developed and patented in the disease-ridden swamps of 1890s New Orleans: the Clayton apparatus. And so while the story of this technology begins as response to the threat of yellow fever in the American South, maritime fumigation quickly became a global project in the context of the third plague pandemic (1894-1959). The promise of the machine was to eliminate microbes, insects as well as small animals quickly, economically and without any damage to goods in the holds of the vessels. A simple furnace, attached to a ventilator, the Clayton could exchange the air of enclosed compartments with SO2. By 1905, the apparatus would be installed in ports across the globe, pioneering the emerging paradigm of complete maritime disinfection, disinfestation and derealisation – a sulphuric utopia of a world of seamless trade without the risk of communicable diseases. As the book shows, however, far from claiming a monopoly on maritime fumigation, the global distribution of the Clayton unfolded within the context of a persistent competition with other innovative technologies of fumigation, whose promised efficacy both praised and strongly contested. Our book explores this overlooked but historically crucial practice at the intersection of epidemiology, hygiene, applied chemistry and engineering. It posits maritime fumigation at the pivot of the emergence of visions and practices of modern sanitary globalisation.

Q. What drew you to the subject and what do you find particularly interesting about it?

The book emerged out of the ERC project Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic (2013-2017, CRASSH, 2017-2018 CRASSH & University of St Andrews), which was led by Christos and where Lukas was employed as a post-doc. Over the course of the project, which examined photographs of the pandemic, we kept finding references to this rather strange apparatus in archives around the world, from Porto to San Francisco, to Hawaii, Buenos Aires and Hong Kong. We realised that this was indeed a history that neither historians of quarantine, nor historians of economy and global trade had picked up and most of the details of this story were entirely new to us. It was also intriguing to both of us to see how this history of a technology and of an apparatus brought together so many different historical perspectives on this period, bridging medicine and trade, laboratory science and colonialism, chemistry and technology, as well as epidemiology and transnational policy. We had more than enough material to develop this history in book length and a fellowship at the Fondation Brocher in Geneva allowed us to develop a well-structured manuscript, which found the generous support from Katie Helke at MIT Press.

Q. What was it like to co-author an interdisciplinary book?

We found the collaboration to be a highly productive process. Most chapters were drafted by one of us before the whole manuscript went through multiple rounds of editing and revisions carried out by both of us. It was wonderful working together on this, and bringing together historical and anthropological perspectives on a truly interdisciplinary analysis. We were keen to deliver an accessible story that does not require expertise within a single discipline or field, but we also wanted to make sure to keep the subtleties and many contradictions of the global distribution of the Clayton apparatus alive. As a result the book contributes theoretically to the concept of a sulphuric utopia at the dawn of the twentieth century while it also comes equipped with an extensive historical apparatus.

Perhaps we found this a particularly productive material to work with as it not only emerged out of our ongoing work on the plague, but also paved the way for research projects we have developed since. The history of sulphuric utopias intersects profoundly with the global war on rats (Christos) and sets out the scene in which epidemiology takes shape as a new global scientific project (Lukas).

Q. The Guardian has listed Sulphuric Utopias among the 30 books that can help us understand 2020. In your view, wherein lies the book’s main contribution to our understanding of epidemics and their control?

Since the nineteenth century, epidemic control has depended upon the application of specific technologies such as disinfection, contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, vaccination and serotherapy. At the same time, however, epidemic control has also relied on the projection of an image of such technologies and techniques as part of an unstoppable process of scientific progress, leading oftentimes to what we may call a technological fetishism in the realm of public health: a tendency to invest hope to machines or technologies in a manner that sidelines the importance of community participation, grassroots innovation and social responses to epidemics. We see this today with COVID-19, where technologies like track and trace per apps or a future vaccine are presented as the solution to the pandemic, to the exclusion of community-led or participatory approaches to epidemic control. Sulphuric Utopias shows us how such investments on fumigation technologies were already at the turn of the century intricately interlinked with approaches that prioritised the market as what is worth being saved and preserved in the context of an epidemic. And at the same time it shows how these technologies persisted through their constant failure, in other words, as technologies that never quite achieved their task but did not completely fail either, thus fuelling their constant reinvention. Reflecting on the development of maritime fumigation technologies is helpful for putting epidemic control efforts against COVID-19 into perspective, and fostering similar critical interrogation of anti-epidemic technologies in use today.

Q. What would readers be surprised to learn about in your book?

There is a dark underside to the story we tell in the book. The search for the optimal method of maritime fumigation did eventually lead to the use of a new gas for the control of plague-carrying rats in the holds of international liners. This was the technology that would eventually defeat and replace the Clayton machine. It was also the technology that would enable the Nazis to undertake the extermination of Jews during WWII. For the gas employed in ports since the mid-1920s and in Nazi concentration camps was no other than Zyklon B. Our book ends with this dystopian point: the drive for a hygienic utopia aimed at liberating trade from the delays of quarantine and keeping ports and cities free from infectious diseases ended up facilitating the technological realisation of the Holocaust.

Sulphuric Utopias was Published by MIT Press in March 2020 and is available Open Access through the generous funding from Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.