Postdoctoral Research Associate Dr Sami Everett recently co-authored a study on Jewish-Muslim interactions and narratives in E1/Barbès with Dr Ben Gidley from Birkbeck, University of London.

Postdoctoral Research Associate Dr Sami Everett recently co-authored a study on Jewish-Muslim interactions and narratives in E1/Barbès with Dr Ben Gidley from Birkbeck, University of London.

The article offers a comparative lens on intercultural and interreligious encounter in urban contexts in France and the UK, focusing on the commonalities and specificities of different national and municipal contexts.

Q. Dr Everett, congratulations on the new publication in Francosphères. What is the article’s primary focus and why is it important?

The article is about two very well known, and increasingly touristic, neighbourhoods in London and in Paris which most people know by a single street name: La Goutte-d’Or and Brick Lane. Local residents tend to call them differently, referring instead to “Barbès” or “Bes-bar” (in verlan*) and E1 or Tower Hamlets; thus the title of the piece. We make this point because we try and show that it is important to understand a neighbourhood, what is thought and said of it and its history, through the eyes and words of its inhabitants and workers. This is called urban ethnography and it is the methodology used by Dr Ben Gidley and I (him as a Sociologist and me as an Anthropologist). The reason for choosing these geographic areas is because they have been in the eye of the sociological hurricane, so to speak, for many years, in debates about migration, national identity, and Muslim communities. In other words, there has been a lot of ‘noise’ made about them, and, as is so often the case, this noise often comes from the outside, from simplistic narratives of ‘uncontrolled migration’, ‘a broken national identity’ and theories abound about a violent, radical ‘Islamization’ of working class neighbourhoods. Needless to say both Tower Hamlets and Barbès are densely populated by people who moved there—Protestant French, Ashkenazic Jewish (Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania), and South Asian, particularly Bangladeshi for Tower Hamlets, and Polish, Italian and Ashkenazic, North African and Sub-Saharan African for Barbès: at least, those are the ways the ‘story of migration’ gets ordered. That said, we do not argue that the two sites can be equated to one another.

What Ben and I argue in this is that the story of migration that gets told—the doxa if you will—is successionist, that is, it is a little too narrowly linear and a little too centred on a simple picture of ethnic or national categories replacing one another over time. For example Tower Hamlets, in terms of its Jewish heritage is not simply Ashkenazic: Mizrahi Jews live and observe Judaism there. Similarly, while most of the synagogues in Barbès have a congregation from Morocco and Tunisia or descendants thereof, one synagogue in particular was set up by pogrom escapees from Kislev. Moreover, the existence of these narratives makes these neighbourhoods targets for populist rhetoric and action see, for example the Apéro géant saucisson, pinard (dried pork sausage and wine apéritif) movement in 2010 by fringe hard right groups in Barbès or the EDL marches on Tower Hamlets. Since anti-Muslim hate speech is a leitmotif for these groups and a way of generating a moral panic, it was important for us to show that in spite of negative representations of the other in the everyday which one might presume would distance Jewish and Muslim inhabitants and workers, there are in fact significant commercial interdependences that operate in both areas. We pinpoint these interactions, histories and working relationships in local eateries, music venues, and in the extant textiles industry (leather in E1 and maghribi** dresses).

Q. How did the idea come about and how did you conduct the research?

This written ‘output’ is part of a long-term research agenda that Dr Gidley and I are pursuing in France and the UK that questions certain commonly held sociological ideas concerning the use of national models for social cohesion among non-majority religious groups: the ‘multicultural’ British model on the one hand and the ‘assimilationist’ model of France on the other. Of course in interrogating those ideas we bump up against questions of the interface between the state and religion i.e. secular system of governance. A large and interdisciplinary future to this article is therefore our current research work in progress. But the article also has an interesting history in itself. Dr Gidley and I met in 2015 when he came to a seminar that I organised between Cambridge and the CNRS (National Centre for Scientific Research) on the topic of comparing British and French perceptions of religion and politics with a focus on the local level i.e. neighbourhood organising, interreligious contact, public policy at the local versus the national level. I found that what Dr Gidley had discovered in the marketplaces of E1 broadly mapped on to my experiences with shopkeepers in Barbès in relation to quite banal forms of discrimination which police the linguistic borders of ‘communities’. While stereotyping is prevalent, local Jewish and Muslim working people work closely together and need each other in order for their businesses to work properly. I give the example of the Algerian Muslim seamstress who is integral to Monsieur El Khiyat’s north African dress business.

The time that I spent in Barbès can be divided into my life ‘before’ anthropology as a telecoms engineer and commerce person (prior to having studied for an MA and a PhD in Anthropology and Politics and the Middle East); the process of becoming an Anthropologist which is bound up with one’s thesis fieldwork which I conducted 2010-12; and the postdoctoral work that I did on the sociology of religious communities in Paris 2015-17. Most ethnographers would agree, it takes a long time of being deeply embedded within an area, a community, a family, or a group (of any description) in order to produce an ethnographic account that is of historical and social value and which contains insight. Furthermore, there is a period of reflection, thematization and theorisation that can only really be undertaken after this period ‘in the field’ so the question becomes not so much ‘how’ you conducted your research—which was through a mixture of qualitative methods such as participant observation, hours and hours of informal (“semi-structured”) interviewing, the capture of group conversation, critical interpretation of relevant literatures (about the neighbourhood)—but rather the stages in the process of reflection and writing between the field, understanding the themes to emerge in that time and reading about applicable methodological and philosophical theories to that work. To give you an idea, among the things that helped both Ben and I to articulate the coming together of those elements was our involvement in a French radio documentary series by Ilana Navaro called l’angleterre et la france au bord de la crise de nerfs (England and France on the verge of a nervous breakdown) which you can find below or here. We gave a historical overview of the sucessionist narratives that I mentioned to you, we showed how these play out in the two neighbourhoods and then related these phenomena to the theme of secularism between the two countries.

For 2019 alongside colleagues in Paris Dr Gidley and I have started working on a fully comparative, large scale, cross-city, Franco-British research project proposal to extend these themes. We hope to submit that this year.

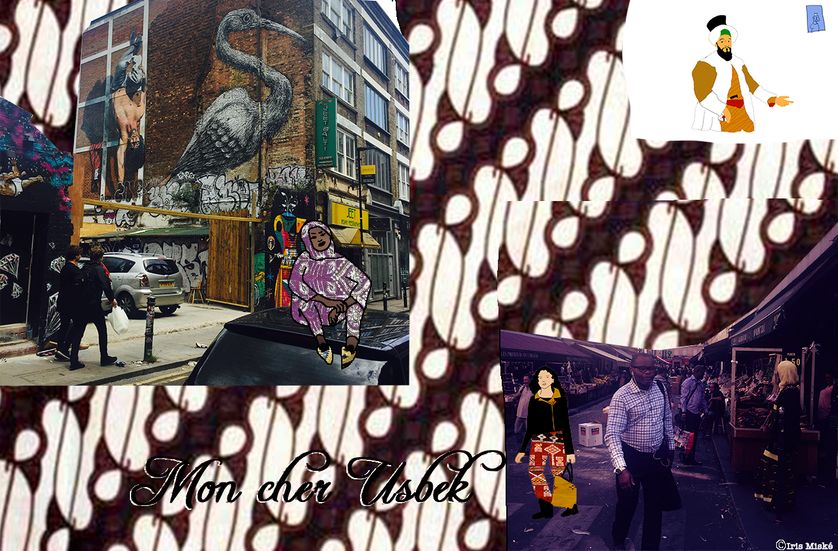

Mes lettres persanes: De Bricklane à la Goute d’Or. Image credit: Iris Miské.

Footnotes:

* French back-to-front slang

** North African dress in Barbès