The current pandemic has in many ways brought the world to a sudden halt. Across the globe many are unable to work, children can’t go to school and the ways in which we used to socialise are no longer safe. Instead, we are trying to engage with the outside world while staying socially distanced from it. One interesting and unintended consequence of this drastic change to our daily lives has been an increase in people’s engagement with citizen science.

Since the end of March when the UK and most countries across the globe went into lockdown, citizen science platforms such as Zooniverse and SciStarter have seen a surge in projects, apps, and participant activity. Zooniverse, for instance, reported that 200,000 participants contributed over 5 million classifications, the equivalent of approximately 48 years of research in one week alone. It seems that teachers, students and even researchers have jumped at the opportunity to receive help with homeschooling and contribute to research programmes. Old and new platforms for citizen scientists have also received increased media coverage, with one plug from The Conversation to ‘Ditch the news cycle—engage, gain skills and make a difference’ and a call for ‘anyone itching for a bit of escapism’ to try citizen science in the Guardian.

This heightened engagement with citizen science has also extended to new projects related to Covid-19 as people are clearly eager to help tackle the global crisis. During this period of piqued interest in citizen science, I want to not only take a closer look at the types of activities that are emerging and expanding but also reflect on the relationship between citizen scientists, experts and policymakers in our pre-and post-pandemic world. What makes this present moment unique and what lessons might it bring to bear on future collaborations between these three groups? Are efforts to engage citizens in tackling the virus harnessing people’s interest to further science as it is practiced, framed and understood by experts? Are the citizen science experiments emerging during this time democratising and pluralising science? I am interested in how the current flux in citizen engagement with science may persist beyond lockdown, but I will also consider how top-down science and decision-making processes still seem to foreground participatory efforts to tackle Covid-19.

How are citizen scientists contributing to Covid-19 research?

Covid-19 presents an especially interesting policy problem because it relies so heavily on population data and mutual trust between citizens, experts and decision-makers. This problem, while not altogether unique, seems to have contributed to the pronounced effort to utilise citizen science approaches for tackling Covid-19. During this period of uncertainty and isolation, logging symptoms, mental health impacts and tracking movement has not only helped experts and policymakers better understand the course of the pandemic but has also given participants a sense of agency. Helpful lists such as the Citizen Science Association’s Covid-19 resources have made it simpler to discover ways to engage and the participation rates reflect an eagerness to do so.

The BBC Pandemic App foreshadowed the types of citizen science efforts we have seen emerge since the spread of Covid-19 began. A project which ran from September 2017 to December 2018, BBC Pandemic was the largest citizen science experiment of its kind and aimed to help researchers better understand how infectious diseases like the flu can spread in order to prepare for the next pandemic outbreak. Participants furthered this mission by contributing data about their travel patterns and interactions. With this data the researchers involved were able to simulate the spread of a highly infectious flu across the UK, and the database is listed as one of the models supporting the government’s response to Covid-19 on the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) website.

Over two years after the study’s conclusion, institutions around the world scrambled to initiate similar studies to better understand the novel coronavirus. The Covid Symptom Tracker has proven the most widespread citizen science effort to track Covid-19 in the UK. Professor of Genetic Epidemiology Tim Spector from King’s College London originally teamed up with technologists Jonathan Wolf and George Hadjigeorgiou to launch a startup called ZOE, which conducted studies on twins and nutrition. When coronavirus hit the UK, the ZOE team acted ‘with a sense of extreme urgency’ to adapt the app to track coronavirus symptoms. The app went live on Tuesday 24 March and by the next day had over one million downloads in Britain. A collaboration between NHS England and researchers at King’s College London, the app was also endorsed by the Welsh Government, NHS Wales, the Scottish Government and NHS Scotland. At the core, however, it is a large scale effort to gather data to be analysed by researchers and then delivered to the NHS and policymakers to make informed decisions.

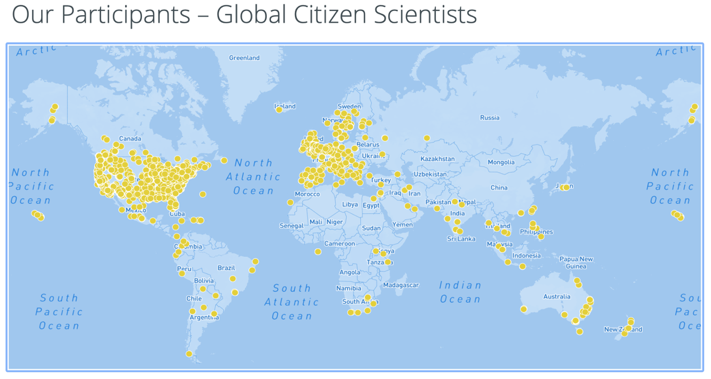

Funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, University of California, San Francisco’s (UCSF) COVID-19 Citizen Science (CCS) has also empowered users to share in the fight against the virus. Popping up in Facebook and Instagram advertisements, the mobile health study has garnered support from people around the world (see map below). The app also offers the option for participants to provide nearly continuous GPS data and potentially additional health data, such as body temperature, exercise, weight and sleep. In late April, Northwestern University and the American Lung Association announced they would be partnering with UCSF in an effort to increase the number of participants and improve chances of generating useful results. The investigators have also more recently invited citizen scientists to submit their own research questions. Receiving more than two thousand ideas, they will soon add these participants’ questions one at a time to the study’s survey.

Points representing CCS participants worldwide. Data source: Covid-19 Eureka platform.

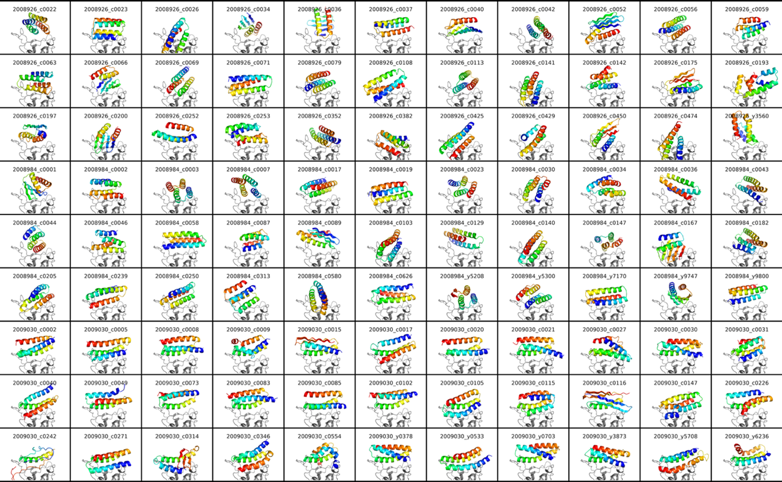

Other citizen science experiments have engaged users more actively in Covid-19 research. For instance, researchers at the University of Washington have used a free computer game Foldit as a platform for citizen scientists to contribute to Covid-19 drug discovery efforts. Developed at the University in 2008, Foldit has previously been used to help scientists in cancer and Alzheimer’s research, but has now seen a pronounced increase in activity since the Covid-19 outbreak. Although it is US-based, the programme has gained traction more widely with the help of promotion by EU-Citizen.Science, and participants across the globe are competing to solve protein puzzles online. Tasked with designing proteins digitally that could attach to Covid-19 and block its entry into cells, participants are aiding the development of antiviral drugs that could ameliorate patients’ symptoms. Researchers involved have found crowdsourcing a helpful tool because of the creativity each person brings to the task.

The 99 most promising of the 20,000 potential Covid-19 antiviral proteins generated by citizen scientists through Foldit that University of Washington researchers plan to test in the lab. https://www.hhmi.org/news/citizen-scientists-are-helping-researchers-design-new-drugs-to-combat-covid-19

A new EU initiative has also invited citizens ‘to take an active role in research, innovation and the development of evidence-based policy on a range of coronavirus-related projects.‘ Supporting a range of citizen science and crowdsourcing programmes, the platform is significant in its broad endorsement of citizen scientists’ contributions not only to research efforts but also to the policy process. Advocating for use of another symptom reporting tool Flusurvey, developed at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and monitored by Public Health England (PHE), the platform is helping to boost responses to existing citizen science efforts as well as publicize the benefits of citizen science approaches more generally.

Closer to home, Cambridge Judge Business School students organised a University-wide 72-hour virtual hackathon #CAMvsCOVID on the weekend 1 – 4 May 2020: ‘One global challenge. One weekend. Your solutions.’ Teams were tasked with drafting ‘a novel response to a pressing problem in the battle against COVID-19,’ with the explicit brief that even coded solutions must consider the societal context. This solutions-focused approach to crowdsourcing harnessed the creativity of the Cambridge ecosystem in a way that other experiments have not; participants were empowered not only to gather data and contribute their research skills, but also to generate potential policy proposals for review. We do not yet know what will come of the ideas generated through this exercise, but it will be interesting to see what comes next.

In what ways does citizen science in a pandemic look different?

Social isolation has prompted many to engage with citizen science who otherwise would not have done so in the past. The urgency of the problem and scale of disruption has set Covid-19 apart from other policy problems with which citizen scientists might generally engage. However, it seems to present a timely opportunity to think about who holds relevant knowledge for public policy and how different forms of knowledge are shared in tackling policy problems.

Despite the complexity of every policy decision made over the past three months, most of us can agree that saving lives and returning to a sense of normalcy were top priorities at the start of lockdown. This unification of goals seems to have set the citizen science experiments detailed above apart from others of their kind. While environmental citizen science programmes covering questions on climate change, air pollution, and biodiversity loss are areas with the largest growth in citizen science over the past decade, they have also presented challenges. Lack of urgency, competing priorities, differing lived experiences and sources of information often create conflicting desires between, say, bird monitoring volunteers and members of the European Council on conservation efforts.

With the outbreak of Covid-19, most agreed we needed to track the virus, understand the science better, develop approaches to containing its spread, support the health system and discover treatments and vaccines to combat it in the future. There was a strong sense of urgency, priorities were more aligned, we recognised these were unprecedented times and there may also have been a greater desire to learn from each other. Though epidemiologists have different knowledge and experience than participants inputting symptoms into an app and both differ from that of policymakers charged with making decisions on behalf of their constituents, these differences seem to have been largely outweighed by the alignment of goals and priorities. Although this has continued to evolve throughout lockdown, these initial conditions enabled greater cooperation and manifested in a proliferation of citizen science experiments.

Differing experiences, information and agendas also breed mistrust, which too often impedes successful collaboration between citizen scientists, experts and policymakers. Can citizen scientists ensure their contributions will be used in their best interest? Will their voices be included in the decision-making process? Can experts and policymakers ensure citizens provide unbiased, accurate data? The global priority to fight the virus from the outset seemed to unify those opting to engage as citizen scientists. The magnitude, scale and consequences of Covid-19 potentially bred a mutual dependence and, in some cases, deference between citizens, research and policy. Amassing data and securing help is crucial for governments and scientists to meet expectations, and citizen scientists will better help themselves by providing accurate and constructive contributions. Trust in the value of citizen science may have been born out of obligation rather than desire during the pandemic, but it is seemingly there.

However, desire and obligation were bound to shift as we moved forward. As Elizabeth Anderson commented in her expert bite with the Expertise Under Pressure Team the issue of trust does not disappear in the context of Covid-19. Trust in shared motives and goals has wavered increasingly as lockdown extends and restlessness grows, and we have yet to find out the consequences of this shift for citizen science.

What does the future hold for citizen science post-pandemic?

As our daily lives gradually come to look more and more like they did before Covid-19, will interest in citizen science dwindle too? There’s no way to know for sure, but I think many will agree that our lives are unlikely to pick up where they left off and the impacts of the pandemic will linger long after the number of cases falls to zero. Although we may in fact be living through a fleeting flux in citizen engagement with science, here are some thoughts on why it may persist:

Support: This new wave of citizen science has clearly seen increased involvement and support of governments, medical institutions and charities involved in the fight against Covid-19. The timing of the launch of EU-Citizen.Science this year has also by no means been a negligible development, as the platform has served to support Covid-19 related citizen science efforts as well as share insights about the potential for citizen science. Although the initiative was set in motion prior to the outbreak, it has been ignited by interest in tackling Covid-19 and could sustain those audiences long after it ends.

Breaking the ice: Motivation to help, extra time and even boredom may be contributing to the increase in citizen scientists’ participation. Desperation and pressure might have caused policymakers to become more open to citizen engagement. However, maybe the unusual circumstances under which the shift occurred are less important than the shift itself.

Funding: The announcement of UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) new £1.5 million Citizen science collaboration grant is another lockdown development that could help shape future directions in citizen science. Funding has long been a barrier to the field. Perhaps the successes of Covid-19 initiatives will prompt more serious consideration of its merits and continue to provide a case for support.

Whether or not increased citizen engagement with science continues beyond lockdown, the nature of more open knowledge sharing between citizen scientists, experts and policymakers during the pandemic is also important to consider. Although we have seen increased trust, cooperation and collaboration, the parameters of scientific inquiry and policy agendas have still largely been set by academic institutions and governments. Rather than enabling citizens to provoke science as usual or express political agency as some forms of citizen science do, the Covid-19 experiments outlined in this blog have predominantly provided platforms for participants to contribute their knowledge to expert-led programmes. The proliferation of participatory initiatives may help to pave the way for more dynamic and experimental citizen science in the future, but perhaps this more fundamental shift in how citizen scientists, experts and policymakers share knowledge is still in the making.

Katie Cohen is a Research Assistant for the Expertise Under Pressure project at CRASSH and at the Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP).