At the close of the nineteenth century, the director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge was M.R. James (1862-1936) — a scholar of early Christian and medieval manuscripts, but also an admired writer of ghost stories. James’ research on the ‘apocryphal’ books of the Bible furnished his contemporaries with knowledge of the late-antique cultures of the Mediterranean, and he would proceed to edit a collection of the earliest and most noteworthy non-canonical texts of the Christian tradition, The Apocryphal New Testament (1924). But with his ghost stories (the most famous of which are published in the collection Ghost Stories of an Antiquary) James imagined and explored the creepy side to such manuscript hunting — such pursuit of history and its objects. His tales feature over-eager scholars, collectors, and antiquarians, confronted with harrowing monsters and ghouls as they open up ancient texts and seek to ask questions of the past.

For his Cambridge connections, for his work on Biblical and Classical manuscripts, and for his imaginative response to the idea that dredging up the past can wreak havoc with our established beliefs and assumptions, the figure of M.R. James popped up very regularly over the course of The Bible and Antiquity in Nineteenth-Century Culture, a major European Research Council-funded project at CRASSH, which came to an end this May.

For in the nineteenth century, discoveries made by scholars like James destabilised the way that texts and authors of antiquity were understood. (Did Homer write the Iliad? Did ‘Homer’ even exist?) And scholarship also called into question the way that the Bible itself was treated as a sacred or authoritative text. Indeed, under the historical-critical method of studying ancient Jewish and Christian writings — a method which focused on questions of authorship, textual sources and genre — the Bible was rendered simply as a document from the past, written by ancient peoples. As Benjamin Jowett was urging by 1860, the Bible should be read ‘like any other book’.

Yet while nineteenth-century scholarship sought to understand ‘the world behind the text’ of the Bible, and to shed light on the of the classical authors, travel, tourism and technology in this period were making far-off places — the lands of the prophets, the pharaohs, ancient empires, and Jesus — closer and more accessible to the public than ever before. Thomas Cook took his first tour to Europe in the 1850s, but by the 1870s the travel agent had also begun organising tours to Egypt and the Holy Land. Moreover, themes from the Bible and from antiquity provided ample material for popular plays, novels (like the best-selling Ben Hur), paintings, sculptures and poetry. In our investigation into ‘Bible and Antiquity in Nineteenth-Century Culture’ then (our project has come to be affectionately known as ‘Biblant’), we as a group have not simply been interested in the drama of textual scholarship and Victorian intellectual life, although this has been important. Rather – a group of historians, classicists, theologians and scholars of English literature – we have also sought to consider how the interface between classics and the Bible loomed large in Victorian culture on a public and popular level. The specific topics taken on by my colleagues have been as wide-ranging as perceptions of the classical body in nineteenth-century art, the Bible and national identity, the circulation and reception of the Bible in colonial outposts of the British empire, and the place of saints and sanctity in nineteenth-century Britain.

In the online exhibition that we‘ve developed in partnership with the Fitzwilliam Museum, you can read and see how the museum’s collections of nineteenth-century items showcase the creative and fascinating ways in which biblical and classical themes captured the public imagination in this period. But over the five years that the group has spent together as a whole, we’ve also run a number of public events. Listing a number of these will give a sense of the scale and breadth of interest covered by the project. In 2013, for instance, my colleagues convened colloquia and conferences on the themes of Anthrolopology and Religion in the Nineteenth Century; Photography, Antiquity, and Nineteenth-Century Scholarship; Visualising the Bible in the Nineteenth Century, and Ernest Renan’s Work and Influence. 2014 then saw events looking at The Biblical and Classical Past of the Nineteenth-Century Novel; The Persistence of the Past in Nineteenth-Century Scholarship, and the Bible, Race and Nation in the Long Nineteenth Century. In 2015 we held conferences on the discipline of Theology in this period; Solomon Schechter’s Life and Legacy, and also on Music and the Bible in Nineteenth-Century Europe. In the final academic year of the project, we then put on events focussed on Theologies of Reading in the Nineteenth Century; Philology (ideals, traditions, methods); Bible and Antiquity in Nineteenth-Century Political Thought; Stained Glass, and Orientalism and its Institutions. Details and summaries of all of these events and their participants are available on our webpages.

The true culmination of the project will be the publication of our projected two-volume book: a collaborative effort featuring work not just from members of the project, but also from visiting fellows and scholars who have spoken at our events.

I have only been a part of the group for just under two years (I was happily hired to replace another postdoc going on to a lectureship post elsewhere), and so cannot possibly hope to speak for the whole five that it has been running. To learn from my colleagues in our weekly meetings together has been a joy, however, and this (fairly) young theologian has been challenged to constantly see things from other perspectives (classical, historical, literary). The world hasn’t heard the last of Biblant!

Captions

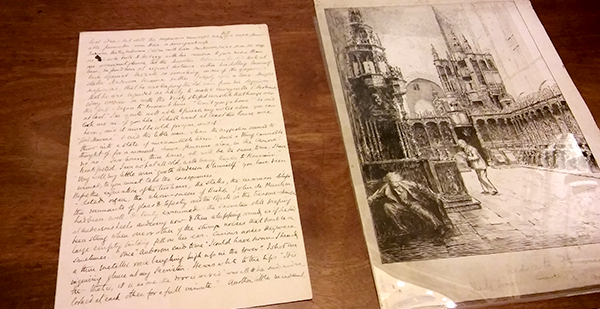

Image 1: handwritten manuscript of the M.R. James ghost story ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook’, with original illustration, borrowed from King’s College Library

Image 2: our director, Simon Goldhill, reading M.R. James’ story ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook’, from Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, 1904

Image 3: some of the group outside Birmingham Cathedral in 2016. We were there to see the gorgeous stained glass windows, designed by Edward Burne Jones

Image 4: some of the team in Birmingham, in 2016

• This research project was supported by funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC grant agreement no 295463.