Introduction

Tensions between politics, culture and the work of generating evidence to inform action were played out in the recent CRASSH film workshop at St John’s College.

The workshop was based on the film Sorry We Missed You (2019, director Ken Loach), which explores our current zero-hours ‘gig‘ economy and its effect on families. The showing sparked discussion on how inequality in health is held in place by many aspects of life. These include precarious employment and household economic stress, their impacts on parental and parent-child relationships, and transmission of mental ill-health across generations. The film is a modern parable. It warns how today’s society is so fraught with the challenges of trying to survive harsh economic times, that it can lose sight of what is fundamentally important for human flourishing – the support we receive and can offer through our domestic, work, and wider relationships

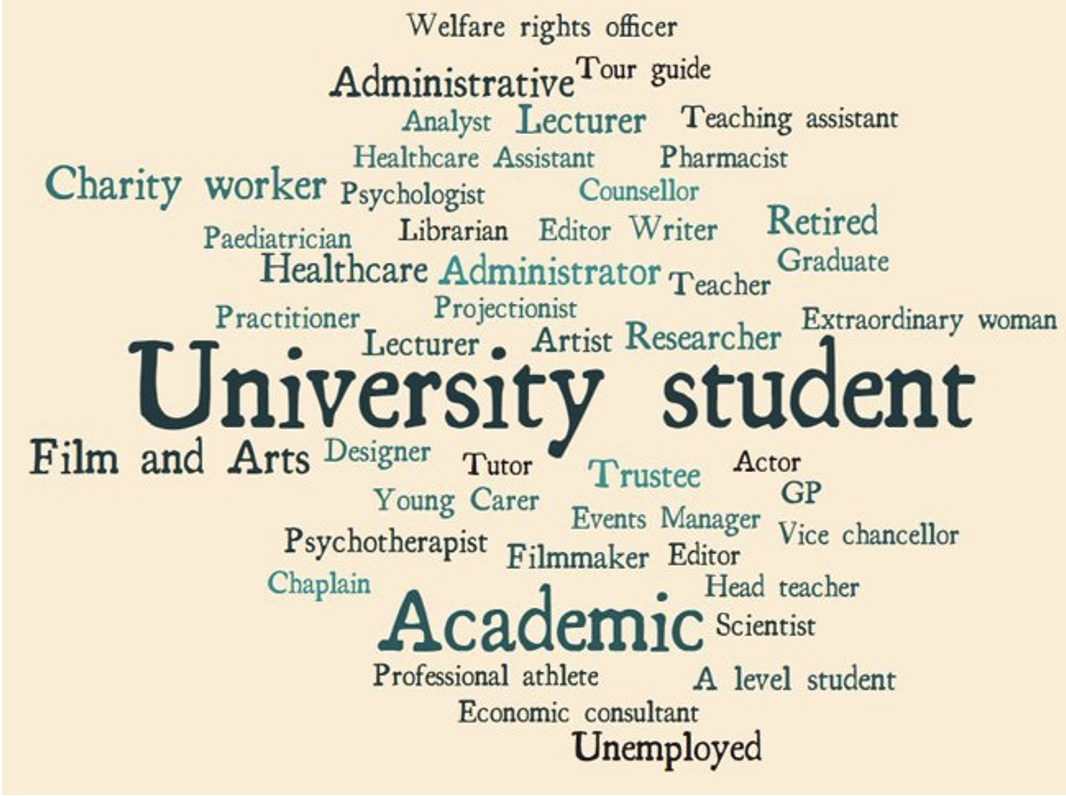

The event attracted more than 100 participants; from academia and film to the worlds of economics, education and charity (see the word cloud below). Together we thought about the relationships between story and evidence, and policy and action to end inequalities in health.

Word cloud from self-declared occupation at event registration; larger print shows dominant descriptors

Robert Gordon, Professor of Italian at Cambridge, began by setting Sorry We Missed You in the context of the earlier neorealist film, Bicycle Thieves (1948, director Vittorio De Sica). He contrasted these two films with classic ‘Hollywood’ films and their expansive stories of glamour, wealth and fast action. Here we find instead working-class lives, depicted in the small carefully observed detail of their every day. In one sense, in these films almost nothing happens (Andre Bazin) – a man’s bike is stolen, a family tries to get by. Yet both films show the struggles with, and cumulative impact of, insecure or precarious employment, that make and sustain inequality.

Gordon drew our attention to the fragile but real sense of community that runs through Bicycle Thieves, set in Italy’s capital city Rome as the Second World War ends. The post-war ideal of a democratic republic, founded on the Italian people and the value of their labour, provides the context. Despite the poverty and isolation of new housing projects, on the edge of the city, there is a sense of community with the union trying to help.

Sixty years later, in the post-2008 world, the struggle to make ends meet persists but the context for Sorry We Missed You includes an increasing sense of isolation and a loss of community support. This film is set in a northern ‘left-behind’ city, Newcastle. A sorrow pervades it; a regret for the disintegration of post-war hopes for a better world. Instead, a delivery worker and his wife, a community nurse, struggle to improve the finances of their family for the sake of their children’s future. This is a story of the failure of the welfare state and fair employment. A story of hard-working parents distracted by insecure work leading to a neglect of their own relationship, and to less engaged parenting of their children who, forced to grow up too soon, are distracted from school and play.

Gordon was asked what impact such films with their ‘little stories’ have on society. He reflected on the tide of writing; of films and of other productions which together describe, embed and ask questions about what in society could and should be better. He depicted film as part of the groundswell of social change.

Sorry we missed you

We moved on to the centrepiece of the workshop; a shared watching of Sorry We Missed You followed by a round table discussion led by Ken Loach, the film Director and Jenny Rankine, Principal of Bottisham Village College

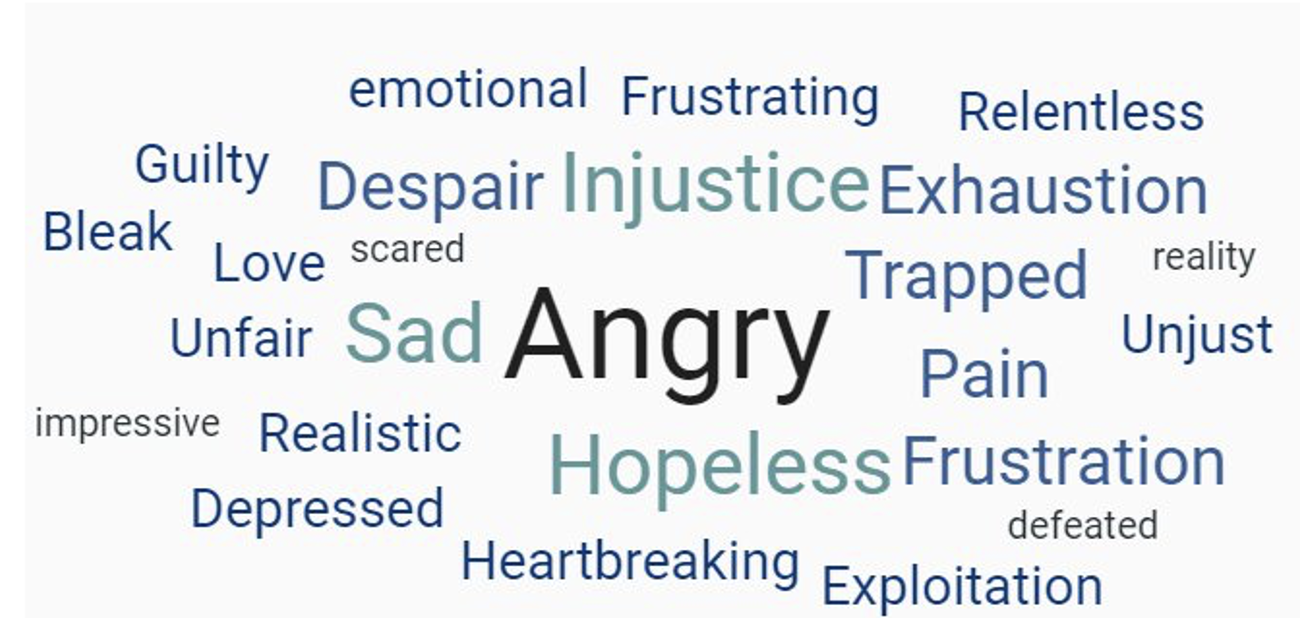

Immediately after the showing, the emotional response of the viewers was captured on Slido (see the word cloud below) showing a range of strong feelings of identification with the characters and their predicament.

Participants were asked to provide ‘three words that come to mind after watching the film’ using Slido immediately after viewing the film

A tea break then offered a welcome opportunity to talk and to bring back to the round table a feeling of discussion continuing rather than beginning.

Loach spoke then, reflecting on the film and more broadly his filmmaking method and motivation. He described the power of collaboration between the producer, the writer and the director in achieving the film. Agreeing with Gordon, he described his films as telling small, authentic stories that shine a light on wider social issues; small stories, but like an iceberg, the reality is underneath. He cited Brecht to explain his aspiration to pierce the heart and demand change with the simplicity of a story and its depiction;

And I always thought:

The simplest of words

Must suffice.

When I say what things are like

It will break the hearts of all.

That you go down, if you don’t fight

Is surely clear to you.

His films tell stories of the working class because they hold the key to our understanding of the enduring class conflict at the heart of society. To understand our predicament you must read history. (Christopher Hill.) For Loach, the conflict of class interest will always prevent the realisation and benefits of a welfare state. It will inevitably promote, and hold in place, precarious work and inequality in health and wealth in families, even as harsh competition between big corporations will hold wages down. He stressed the central importance of strong trade unions and political representation to defend and advance the interest of the working class.

Loach concluded the session by encouraging everyone to join in and organise; whether it’s a charity, a campaign; a union; a political party. His experience is that it is cheering to join together and get organised. It is necessary to organise to make change. Politics is a struggle. There is no middle way. Capital and labour will always be opposed. He asked the audience- Which side are you on?

Rankine then spoke of her school, like so many in the sector, challenged by rising demand and falling resources. She said that every child struggling in the system was a child in the film, referencing it to illustrate the heart-breaking realities facing present-day education. She affirmed the film’s depiction of the emotional toll that precarious work has on families and children; manifesting in extreme behaviours and a breakdown of family structure. She described how these problems are compounded by a lack of early intervention and by teachers, overwhelmed, leaving the profession. She reported that teachers could no longer see a way forward alone, and called for collective action and empowerment of young people to shape societal values and address the clear inequalities facing the poorest members of society.

Local charity workers also affirmed the film and its relevance to Cambridge families as well as to those in the North-East. They called for children to be allowed to be children and not to have to grow up before their time, nor to parent their parents as shown in the film. Every family they help is a success story-feelings of helplessness at a grand political scale can be replaced with hope in enabling families one by one.

Members of the audience also affirmed the message of the film. They gave personal examples of their experiences of exclusion. They engaged in charged discussions of social justice, inequality, and the importance of constructive anger and collective action. They talked about how the middle class is also struggling with rising costs, extending the problems of the film to a broader class base. They lamented the derogatory language still used by those in power, including the media, to describe the working class, and their own experience of a taboo to those with experience speaking out about persistent influence of the class system. They highlighted the need for professionals, such as lawyers and doctors, to support social justice in their communities and the importance of investment in areas affected by industrial decline.

Loach concluded the session by encouraging everyone to join in and organise; whether it’s a charity, a campaign; a union; a political party. His experience is that it is cheering to join together and get organised. It is necessary to organise to make change. Working together will certainly be more effective in reducing inequality than being miserable about it on one’s own and doing nothing.

From story to evidence

Having laid bare the scale of the problem and the multifaceted consequences of precarious work, especially for future generations, the workshop turned to Professor Gordon Harold to consider evidence-based policy measures that address issues highlighted in the films.

Harold discussed his work on the psychology of education and mental health and the strength of the evidence that fostering healthy family relationships could improve mental health outcomes for young people. He presented data from the Iowa Youth and Families Project, which identified economic stress, adult mental health problems, disrupted parenting practices, and interparental conflict as key factors correlating with adverse outcomes for young people. He argued that interventions focusing on adult relationships could improve outcomes for the children. He argued that the antidote to the situation shown in Sorry We Missed You was policy that specifically supported the recovery of positive relationships within families. He signposted the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) Programme, being led by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), as an example of an innovative UK-based policy programme in this area.

Action to end inequality in health

Participants reflecting at, and after, the workshop spoke of the clear need for action to support healthy family relationships and to ground policy in research.

Individuals were persuaded of the need to help break destructive life cycles by supporting relationships, building resilience and encouraging collective action. They underscored the importance of emotion to motivate change based on evidence rather than as an end in itself.

For example, one participant pointed to learning how “Interparental relationships are of great importance – this is fascinating, hopeful, and from my personal and clinical experience makes sense. I will take this evidence into my clinical work”.

This learning was linked to intentions to do things differently after the workshop. Participants spoke of; getting involved; networking, using multimedia, volunteering, joining a collective to drive change; joining in with others to organise; in one’s own workplace, in political organisations; through strike action.

Specific actions were proposed to stop ‘gig’ work and scrutinise online fast-delivery corporations. In relation to Cambridge University, one participant commented “I think in Cambridge we need to question our own position as individuals and the University, in reinforcing and being complicit in, maintaining current power structures and work to change these”.

Several academics shared their view that discussion of working-class values was still avoided at university level. Comparisons between the global position of the University of Cambridge in educational excellence, and the impoverished local state educational environment in surrounding Cambridgeshire, led to a call to understand what relationship existed between the two and how it could be transformed to reduce inequalities.

Participants also thought about how to work with people with different life experiences from themselves, intending to “Try to make more in-depth practice-based connections, as a result of this workshop” and to “Work in the registers of the people you’re working with not in academic languages and corrosive aspects of data.”

The films confront us with living stories of how inequality is sustained. The workshop contributes to a political and social awareness that can strengthen solidarity and collective action to address the causes and consequences of inequality in health and wealth.

In the central example of the transmission of inequality in mental health across generations, we saw the potential of story from film alongside evidence-informed programmes for families and schools, to inform and drive reform.

We can create a society more equal in health and wealth. We choose not to. Can we live with the consequences of doing nothing?

- The workshop convenors were: Minaam Abbas, Ann Louise Kinmonth, Mike Kelly and Helen Watts

- Authors of the workshop report: Minaam Abbas (St John’s College Picturehouse) and Ann Louise Kinmonth (Convenor St Johns College Reading Group on Inequalities in Health)

- Editorial assistance: Helen Watts, Academic Administrator

- We thank CRASSH, St John’s College, St. John’s Picturehouse and our speakers Robert Gordon, Ken Loach, Jenny Rankine, and Gordon Harold.

Resources

- Further details of this and related workshops can be found via the St John’s Reading Group on Health Inequalities | St John’s College, University of Cambridge and the CRASSH conference webpage.

- I Daniel Blake; St John’s Reading Group on Health Inequalities | St John’s College, University of Cambridge

Quoted sources

- Robert S C Gordon 2008 Bicycle Thieves BFI Film Classics

- André Bazan (1967–1971). What is Cinema? Vol. 1 & 2 (Hugh Gray, Trans., Ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02034-0 Copyright Date: 2005

- Christopher Hill 1940 The English Revolution 1640.

Pub Lawrence and Wishart. - Eduard Bernstein Cromwell and Communism Socialism and Democracy in the Great English Revolution (1895) Pub George Allen & Unwin, London 1930/1963.

- Bertolt Brecht poems. eds John Willet and Ralph Manheim with the co-operation of Erich Fried by Brecht, Bertolt, 1898-1956; Publication date 1976; Publisher London, Eyre Methuen,

- Ken Loach Premiere; ‘The Old Oak’ 76th annual Cannes Film Festival 16 to 27 May 2023.

- Iowa Youth and Families Project, 1989-1992 (ICPSR 26721) PIs: Rand Conger, Iowa State University; Paul Lasley, Iowa State University; Frederick O. Lorenz, Iowa State University; Ronald Simons, Iowa State University; Les B. Whitbeck, Iowa State University; Glen H. Elder Jr., University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; Rosalie Norem, Iowa State University (doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR26721.v2)

- Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) Programme.