Is human nature something that the natural and social sciences aim to describe, or is it a pernicious fiction? What role, if any, does ‘human nature’ play in directing and informing scientific work? Can we talk about human nature without invoking – either implicitly or explicitly – a contrast with human culture?

It might be tempting to think that the respectability of ‘human nature’ is an issue that divides natural and social scientists along disciplinary boundaries, but the truth is more complex. CRASSH Communications Manager Imke van Heerden asked Tim Lewens, Cambridge Professor of Philosophy of Science, to tell us more.

Q. Tim, what was your role at CRASSH and how long were you affiliated to the Centre?

I was CRASSH’s Deputy Director. My three-year term there ended just under a year ago, in August 2017. It was a terrific experience: intellectually enriching, punctuated by some remarkable public events, and all orchestrated by a wonderful team made up of people such as yourself.

Q. You are co-editor, with Elizabeth Hannon, of the collection of new essays Why We Disagree About Human Nature. How did the book come about?

It’s CRASSH again: the book started life in a conference of the same name held in CRASSH back in December 2015. It was one of the most significant events that we undertook as part of a large ERC-funded project called ‘A Science of Human Nature?’. Beth Hannon, my co-editor, was a member of the project team for the first few years of that project, but has since gone on to bigger and better things: she’s now Director of The Forum, an educational charity that puts on some of the country’s most interesting philosophical events targeted at the general public.

Q. The collection includes contributions from scholars working in many disciplines. How do these diverse perspectives help us to understand, or approach the subject of, human nature?

There are some surprises among the contributions. For example, you might assume that thinkers with backgrounds in evolutionary theory would be enthusiastic about the idea of human nature. It turns out that these contributors are split: some of them argue that there is a respectable notion of human nature, which acts as an important target for the human sciences to describe. Others – still with expertise in evolutionary sciences – think the idea that humans have ‘natures’ is scientifically outdated or misleading. What’s more (and this maybe won’t be so surprising to people familiar with work in social anthropology) our sceptics do not usually try to undermine the notion of human nature by appealing to the greater importance of culture. On the contrary, our sceptical contributors often end up denying the value of the notions of both ‘culture’ and ‘nature’.

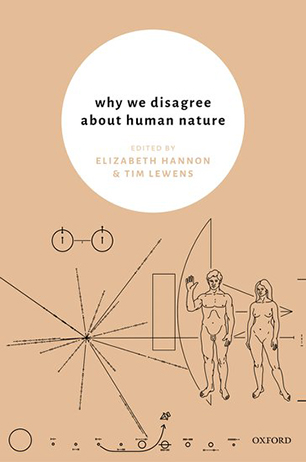

Q. Can you explain what the picture on the cover is, and why you chose it?

Sure: it shows the plaque that accompanied Pioneer 10 when it was launched in 1972. It was bolted onto the side of the probe, just in case it should travel far enough to fall into the hands of intelligent aliens. We chose it because it helps to show why human nature is such a contested concept. It’s tempting to think that there’s nothing wrong with supplying intelligent aliens with pictures of a typical human male and female, in just the same way that our own field guides give us images of typical male and female blackbirds. But if the function of these images is to help intelligent aliens pick out the humans among all the other organisms they might encounter on a visit, why are the man and woman pictured without clothes? Perhaps the images are meant to represent how we are by nature, stripped of cultural influences. Many of our contributors are interested in whether it makes sense to contrast nature and culture in this way. And why is the man given the job of greeting the approaching alien, while the woman seems turned slightly towards the man? The image draws our attention to the ways in which representations of supposedly universal features of our species can, at least sometimes, be reflections of much more local suppositions of the people who produce those images.

Q. Where might one find a copy of the book?

It’s one of those academic tomes that probably won’t make it to airport bookshops. You can get it on Amazon – and right now there is even a 13% discount!

Bonus question (if you dare): Please summarise the book in a tweet.

Ooooh, that’s tricky, especially given that the chapters all express different positions. (Also, I’ve never written a tweet in my life.) How about ‘Whether you are a friend of human nature or a foe, this book will make you rethink your views.’