‘Wonderful Songs’ resonating with traditions and art

They [the Tolteca] went about using the ground drum, the rattle stick. They were singers; they composed, originated, knew from memory, invented the wonderful songs which they composed.

– Quititlantihui in huehuetl, in ayacachtli, cuicanimeh catca, quipiquia, quizaloaya, quilnamiquia.

(Sixeenth-century transcribed Nahuatl from the original based on Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble’s the Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 10—The People, Bernardino de Sahagún (University of Utah, 1961): 169.)

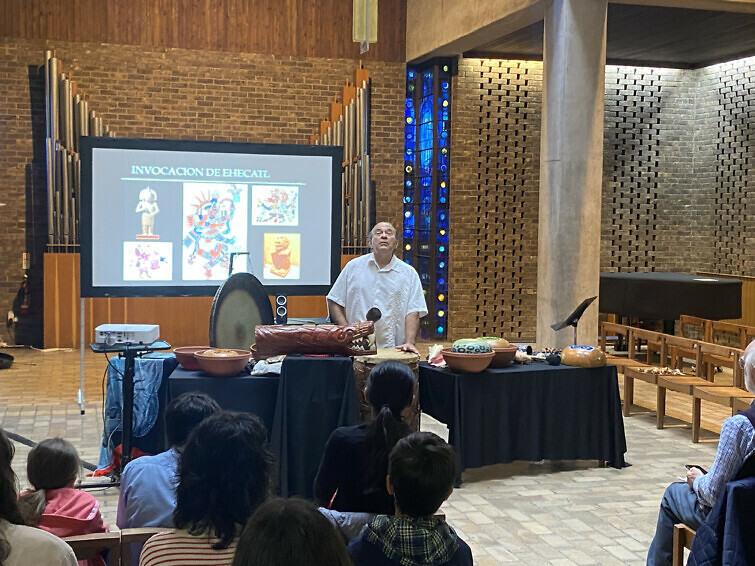

On Tuesday 4 July 2023, the Cambridge community was invited to enter the Chapel at Churchill College to hear sounds and words mostly unknown in the UK, and to learn of the resounding messages given to them by a world-class musician and educationist. The event formed the second part of the 2023 Multicoloured and Melodious Dimensions of the Americas: Music, Colour, and Craft Playshop and featured the talents of Christopher Garcia. A trained percussionist specialising in Indigenous instruments from around the globe, Garcia’s rhythmic focus that night was trained upon Mexican heritage soundscapes. One guiding reason for his visit was to answer the question: how can we help to advance the connections we might have to art, languages, and innovative research about the past? Garcia’s rejoinder included playful discovery and immersive learning opportunities. He full-throatily performed for ninety minutes, breaking on occasion to describe each instrument and tell penetrating stories. The dozens of instruments Garcia brought included membranophones, ideophones, and aerophones—each a mnemonic of the ancient roots of musicality in the Americas—and the intimate space became conducive to the study of Garcia’s concept of resonancia (‘resonance’). This resonance can contain enduring memories, too, as witnessed in the above passage from the Florentine Codex, an ethnography of the Mexica people and other Indigenous peoples of the Americas recorded in the sixteenth century.

Furthering Cambridge’s ethnolinguistics

The core purpose of the event was to continue to foster public inquiry into the archaeology, art and history of the Americas, in this instance via music and craft has been the mission of the Americas Archaeology Group with the McDonald Institute and the CRASSH Multidimensional Dialogues (MD) research network. Garcia’s play-and-present style contributed immensely to the motivation of understanding the legacies of living traditions, keeping them alive, and experiencing the sights, sounds, and artwork that once echoed in the past. The event built upon our group’s work with Escuelita Cambridge and, sponsored by a CRASSH workshop grant and Cambridge Language Sciences Centre’s Impact Fund, it focused on the importance of language too. Garcia’s ethnomusicology is most focused on Nahuatl (a living language throughout North America and once the lingua franca of the ‘Aztecs’) and Maya terms for objects. The research is based upon a database he has in development but also from the years Garcia has spent sharing songs in Nahuatl, Spanish and English.

A regular performer in Mexico and the US, Garcia has played with community elders and youths whose lives have crossed or been crossed by national borders, with musical coherence often generated in the sharing of terminologies and local styles of play by multi-generational specialists. Learning with linguistics, Garcia explains, diversifies how one interacts with the instrument. The star of the event was the large, wooden drum, called a tlalpanhuehuetl in Nahuatl (‘earth drum’) and Garcia played a replica of one in the Malinalco Museum (crafted by Jaime Flores). The Multicoloured and melodious dimensions playshop was fortunate to have been provided with this by Ian Musell, Director of Mexicolore.uk.co.

The huehuetl, a massive upright barrel-like drum, is made from a hollowed cypress log and, traditionally, covered at the top by a membrane of deer or jaguar skin. The word may refer to the ahuehuetl tree, but Garcia explained that ‘huehue-‘ also could connote an ancestor, something inherited from one’s elders, or be a person’s name. Letting us listen to the base thumping play of the tlalpanhuehuetl, Garcia linked the impermanence of one’s heartbeat to memories, some traumatic and others therapeutic. During the song called ‘Toxcatl’, Garcia pounded out a profound intensity in remembrance of the Toxcatl Massacre of 1519, when defenceless Mexica musicians were cut down whilst performing an annual festival during the Spanish invasion.

For ‘Mayan Children’s Song’, Garcia featured several instruments in quick tempo. This included the horizontal slit drum, what the Yucatec Maya call the tunkul and the Nahuas the teponaztli. Garcia’s teponaztli features a brilliant red rendition of a dragon-like creature he named Quetzalcoatl, after the plumed serpent of the Nahuas, whom Yucatec Maya call Kukulkan. Another ideophone was less impressive on the surface but shocking for those having never before encountered them. The turtleshell drum (kayab in Maya; ayotl in Nahuatl) was played by scraping a deer antler across its underside.

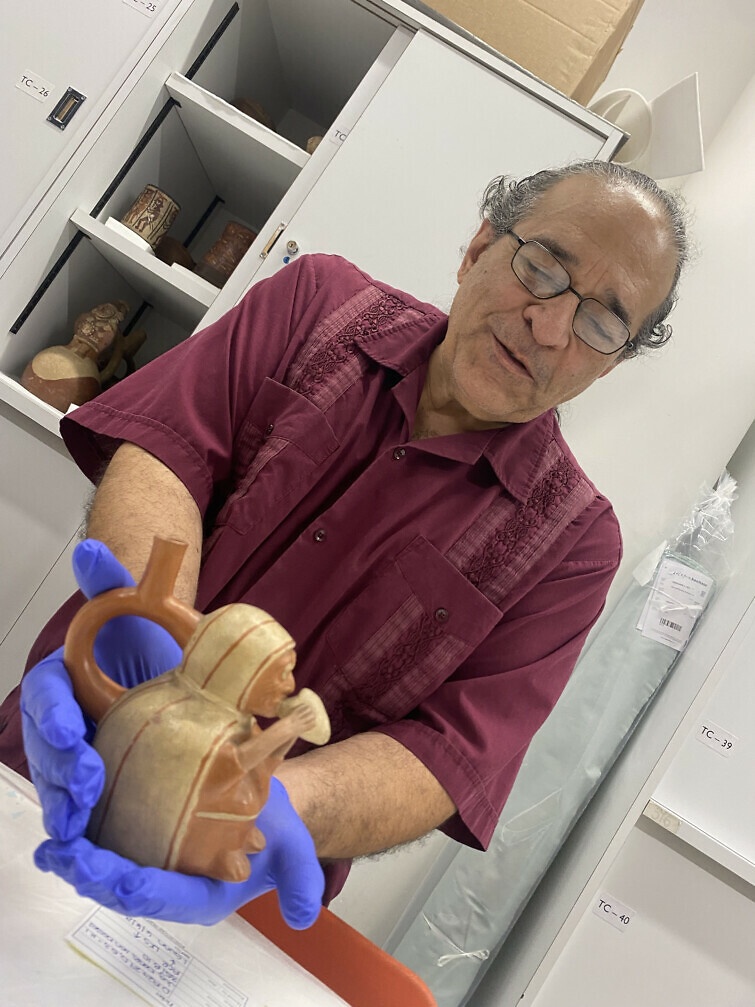

Breathing life into the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s collections

The latter portion of the evening focused on Mesoamerican aerophones. Garcia played several ceramic flutes or tlapitzalli. The younger audience members giggled with the surprising roar when he blew through the conch shell (tecciztli in Nahuatl). One controlled the instrument with breath, buzzing one’s lips, covering the hole drilled into the shell, and cupping a palm over the shell’s opening. Garcia explained that the musicality of the tecciztli dramatically transformed with both the tool, performer and the environment of play. His was a simple white version, but the oldest examples could be highly-decorated and intricate, featuring clay mouthpieces, feathers, and paint. The earliest examples are found in the murals of the grand city of Teotihuacan, where imagery of feline figures play versions of the tecciztli with inventive mouthpieces, as seen in the photographic collection at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA). Garcia recently had the chance to hear the echoes of the conch’s trumpeting of the site’s walls.

Following the playshop, thanks to the support of the MAA’s staff, Garcia made time for a bit of collections research. This included an up-close study of a flute with an endpiece in the likeness of a vulture. This object is believed to have been made by Nahua artists, likely from Isla de Sacrificios, Veracruz, in the Postclassic period (1200 -1520 CE; MAA 1924.330), according to the catalogue. Resisting the urge to play it, Garcia noted that the sounds of many flutes could be designed to mimic animal calls, especially bird calls, thus colouring our interpretation of the object’s avion headpiece. The finger holes would allow for varying degrees in pitch and, most likely, the sound would be melodic. But might someone have once played the vulture flute to sound like an actual vulture? Garcia decided to leave that question up to the next Americas-based musicologist to determine.

The art of play

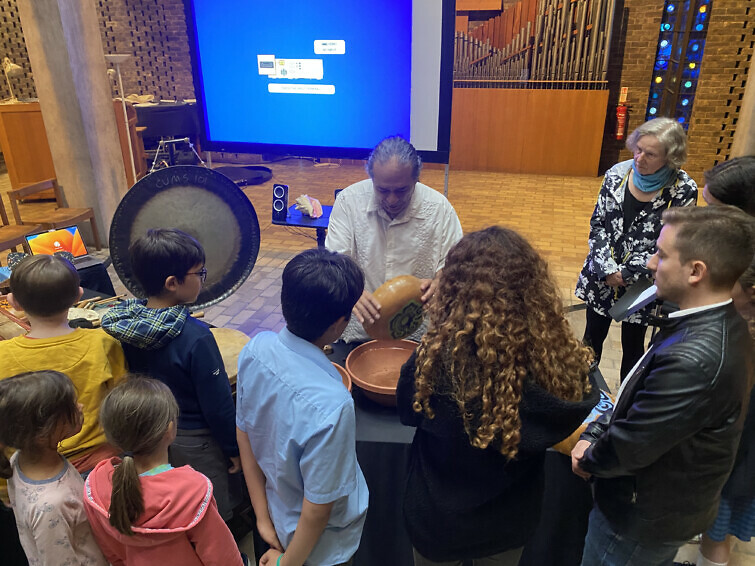

One takeaway related to Garcia’s brief explanation of the water drums, called baa wehai, a set of hollow, upturned gourds that were floating on water in large bowls. This instrument is tied to the living traditions of the Yoeme (commonly ‘Yaqui’) people of Mexico’s northwest and the Sonoran Desert. Called the baa wehai, the drum symbolises an inextricable connection between humanity, art and sustenance. The tens of thousands of descendant community members who speak the language are the only keepers of what the water drum truly means. For an example of the language, you can listen to a recent recording (including English/Spanish translations) by Yoeme Jenny Murieta.

Today, a top priority for the Yoeme is maintaining access to clean drinking water as they confront man-made climate change. Struggles among the community can lead to less inclination to keep up traditions and language study–a concern for any of the endangered languages of Mexico. Hoping to educate and draw awareness, Garcia’s playing of the baa wehai in the Chapel at Churchill College can inspire intercultural awareness whilst expanding the soundscapes commonly heard in Cambridge. He explained that for the Yoeme playing the baa wehai will bless the water in the bowl, charging the liquid with power from the songs. It was necessary to pour the waters over the earth and gardens, not simply down the sink.

Garcia also brought whimsy with his visit. At one point, he produced a long wooden rasp, an instrument seen painted on polychrome pottery from the Classic Maya. Placing it atop a gourd and slowly stroking it with a stick, Gracia soon filled the room with a full-throated growl of the North American Jaguar. Surely this was a first for Churchill College. Garcia also demonstrated that modern art, too, has a resonance. Whilst studying Barbara Heppworth’s Four-Square (Walk Through) 1966, a centrepiece of College, the instrumentalist briefly played the sculpture with his hands. One might pretend Garcia was tapping out an impromptu rhythm within a massive, bronze tlalpanhuehuetl.

Voices in the crowd

The MMD Playshop 2023 event’s guests strongly recommend you attend more events of this sort. This is based upon data from a voluntary survey offered to all audience members, of which one-third of attendees responded. These reactions, beyond documenting perspectives on the event, will help guide future programming thus helping to shape Americas-related programming in Cambridge moving forward. In the short survey, questions ranged from gauging the respondent’s experience on a preference scale (i.e. ‘poor’ up to ‘excellent’) as well as open-ended prompts to allow descriptive answers. Respondents most liked the variety of instruments Garcia introduced us to (more than 12 on hand) and the welcoming atmosphere provided by the presenter and co-convenors. Had you attended, it is likely you would come away with a shared desire to study one of the specific instruments in more detail or delve into the History of music of the Americas. Closing the event was an enjoyable questions-and-answer portion wherein audience members explored the instruments up close, and Garcia further encouraged intercultural musicology for young and old.

Please come join the dialogue next year!

Thank you from the Americas Archaeology and MD CRASSH team: Joshua Fitzgerald, Jimena Lobo Guerrero Arenas, Oliver Antczak, Chike Pilgrim, Jasmine Vieri, and Camila Alday.

Prepared by Joshua Fitzgerald on behalf of the MD CRASSH research network 2022-23 and Americas Archaeology Group, Cambridge.