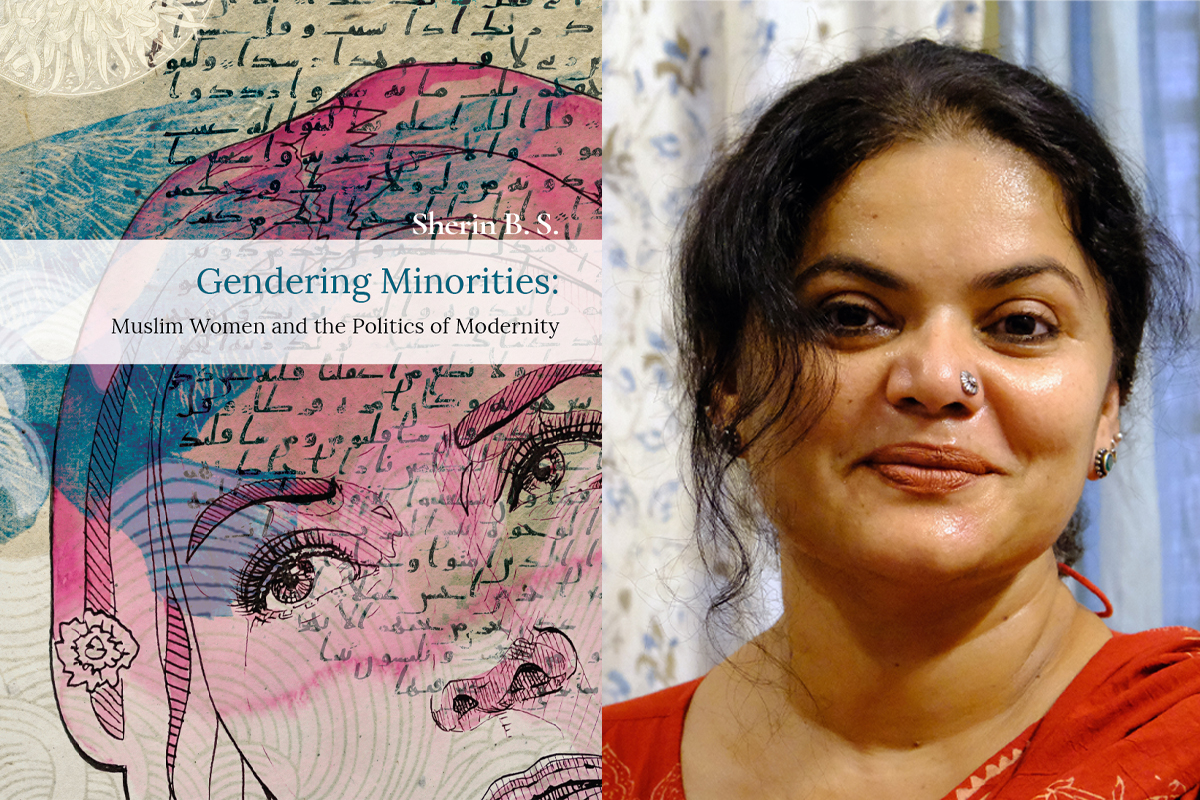

Sherin Basheer Saheera is Associate Professor at the Department of Comparative Literature and India Studies, The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, India. She is CRASSH’s Charles Wallace India Trust Fellow for 2023-24.

Q: What is your book Gendering Minorities: Muslim Women and the Politics of Modernity about?

Over the years in India, Muslim women as political subjects have been constructed through discourses surrounding the demand for a uniform civil code and the reform of personal laws. This image is ahistorical; in Indian reality Muslim women’s status and public life have gone through tremendous changes historically. Strange alliances between a) right-wing nationalism’s construction of Muslim women’s victimisation by religious patriarchy, b) the critical position taken by the Left on minority religious identities, c) the feminist clamour for justice for Muslim women which easily plays into global imperialist islamophobia and d) the right-wing targeting of the community, mark the premise from which this book attempts to re-frame Muslim women as nuanced political subjects.

Q: What drew you to the subject and what do you find particularly interesting about it?

This book came out of my doctoral research on women and Islam in South India, where I had closely engaged with Muslim women’s organisations, and community platforms and also worked with literary and other discourses on Muslim women, drawing from anthropology, literary and comparative studies. My expertise in the study of Muslim women and familiarity with the community helped me to explore the living realities of Muslim women in India. I have published extensively in relation to the contemporary legal debates on Muslim women’s rights in India. My intention was to explore an archive to politically engage with women in religious communities. As a South Indian Muslim, I have experienced the sheer laxity in legal and feminist discourses, while addressing the complexity of Muslim women’s rights. By showing the distance between the ideal modern rights discourses and aspirations of women in Islam, my intention was to revamp the political discourse on Muslim women, providing a strong archive challenging the western/modern perception of rights.

Q: Around which themes did you decide to structure the book, and to what end?

The study is located in Kerala, India, a state that has a different political history from the rest of India. Within the contexts of early proselytising movements, early twentieth-century reform movements and as subjects of active debates on women’s agency Muslim women unravel a life-world of complex realities. The texts gathered in this archive straddle generic boundaries and cut across disciplines and periods in history. There are discussions of literature, journal entries, tracts, historical documents and oral narratives that provide insight into women’s articulation, participation, defiance as well as their sense of community. Each discussion pays special attention to the contexts in which the ‘texts’ originate, and embarks on the question of Muslim female subjectivity in Kerala.

This is an effort to knit together various instances where Muslim women have been powerful agents of their action and not mere subjects to the norms of a homogenous religious patriarchy. It is important to acknowledge these agential acts as a counter-narrative to current ‘feminist’ misreading and ideological distortions. Various chapters look at Muslim women’s role as Sufis, rulers and local practitioners in the spread of Islam, conversions and the formation of community, and as political agents in the early twentieth century reform movements. Countering the victimised status of Muslim women in recent feminist discourses, the book probes further into the problematic contemporary assemblage that brings feminists and right-wing Hindutva groups together. It urges feminism to take notice of practising Muslim women from a totally different angle, incorporating their faith.

Q: In your view, wherein lies the book’s main contribution to our understanding of Muslim women in India?

My engagement with women and Islam in Kerala presents Muslim women as subjects of differently conceived notions of the religion, shaped by different factors of time, region, class, ethnicity, etc. I try to present a heterogenous subject, whose agency is not determined by a singular political formation. Liberal secularism may think of Muslim women’s agency as religious conformism. As I have stated in the book, the imaginative possibilities of left liberal thoughts on Muslim women centre around misogyny and patriarchal violence. While it is important to think about Muslim women in the context of diverse practices within Islam, my analytical focus mainly centres around the identity of Muslim women, marginalised by discourses on nationalism and liberal thrusts on individualism.

Q: What would readers be surprised to learn about in your book?

As pointed out in the preface, the book makes some significant methodological shifts in studying Muslim women in India. The context of Kerala, with a sizeable Muslim population has never come up in analysis related to Islam and women in India before. Thus, through foregrounding Muslim experience in Kerala the book tries to focus on regional variations in practices and politics. Further, the legal debates and personal law questions often taken up in discussing Muslim women in India are not the focus of this book. It looks at cultural texts, that involves Muslim women’s agency, motivated not by an abstract idea of women’s freedom and individualism, but through acts that take into consideration social positioning of the community, the predicament of Muslim men and also the faith in Islam.