Caroline Bassett is Professor of Digital Humanities at Cambridge University’s Faculty of English, Director of Cambridge Digital Humanities, and a Fellow of Corpus Christi. She is also a member of CRASSH’s management committee.

Q. Caroline, what is your book Anti-computing: Dissent and the Machine about?

Anti-computing sets out to explore hostile or dissenting responses to the rise of the computer, and the apparently unstoppable expansion of computerised culture. The book ranges across the late 20th and early 21st century, arriving more or less in the present day. It’s a cultural history of a kind – one that responds to the impossible scale, pace and expansion of the computational, and its suffusion into all aspects of life. I wrote it because I wanted to understand why hostility to computing recurs and what shape and form it takes – in specific moments and across time.

The book binds up two lines of inquiry. I focus on particular instances of computational dissent, explored on their own terms and in their own time. I’m interested in what anti-computing looked like to a philosopher encountering cybernation debates in the US in the 1960s; to a black-lister turned counter-cultural activist slightly later; to F.R. Leavis, speaking from the ‘other’ side of the Two Cultures debate; to an MIT scientist committing apostasy in the temple of technology when his own code spoke back to him; to feminist SF writers responding to 1990s cyberspace; and in Weird literature preferring the flesh to the machine. Amongst other things…

The second line of inquiry asks what links these instances. I wanted to identify what is familiar or recurrent about the forms that dissent takes. I argue that anti-computing doesn’t develop linearly so much as recur erratically yet also predictably. For instance, concerns around surveillance, freedom, the hollowing out of human creativity, digital discrimination and bureaucratisation rise up then fade away, but later find new salience and intensity as new constellations arise. Today, for instance, where rapid advances in AI converge with shifts in the global political landscape to fuel forms of disenchantment with platforms, we can see forms of anti-computing emerge, specifically addressing new developments (machine learning for instance), but also resonating with earlier formations.

My interest in thinking about how computational technology – or technical media – intervenes in the temporality and organisation of these recurring circuits has led to an engagement with media archaeology, here viewed, perhaps heretically, as a form of cultural studies. One of my concerns in the book has been to ask how we can better understand and theorise technological change as cultural politics.

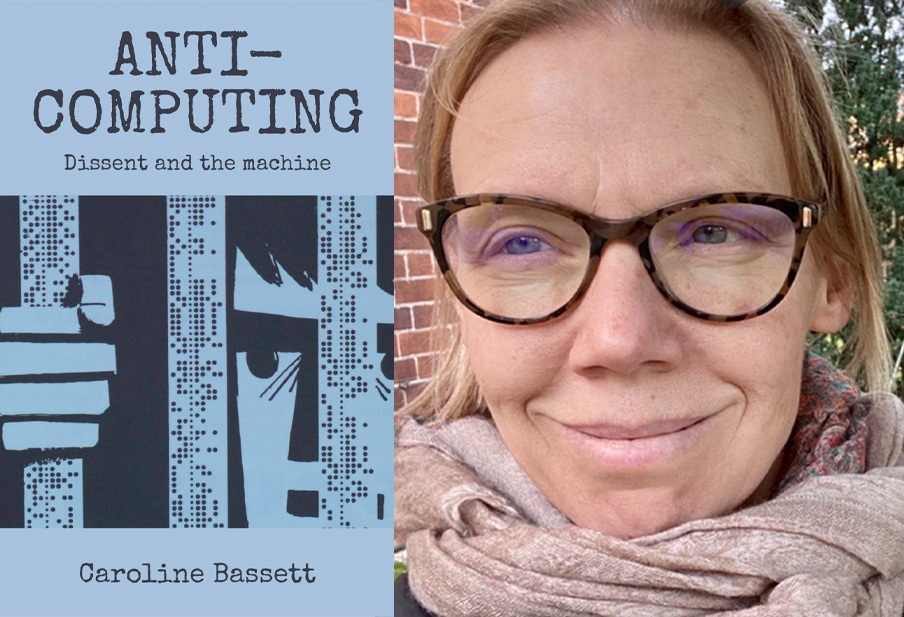

Caroline Bassett and the cover of her book ‘Anti-computing’

Q. What drew you to the subject and what do you find particularly interesting about it?

I have been interested in automation histories for some time, engaging with critical theories of technology on the one hand and with resistant forms of practice and engagement with digital technologies on the other. This project began partly because I wanted to think about what linked these two lines of research – and what didn’t. It also seems increasingly important to me to recognise ‘the internet’ as a historical formation not least because the tech industry invites us to stay in the present or endlessly look forwards to the new – to upgrade our machines and ourselves. The specific focus on dissent came about partly because the form in which technologies come to us, how they are delivered, or sold, what they promise to do, can easily appear to be the only form possible. In this context, it is important to understand that on the contrary there have been other ideas about how they should be developed and integrated into different societies and cultures, and different understandings of for whose benefit this might be. And cultures. A major influence in the book is also Hannah Arendt’s Human Condition, which seems to me to begin many of these debates and to bear directly on cybernation this time around.

Q. Around which themes did you decide to structure the book, and to what end?

I wanted to find a way to explore dissent, anxiety, unease – a cluster of responses to the rise and rise of the computational across its early to current decades that are characterised by a certain kind of refusal, or perhaps by a way of looking awry. This was partly because these responses – organised, circulating, variously powerful – are frequently neglected. There’s a great deal of attention being paid to contemporary dis-enchantment with technology (fake news, monopoly, AI anxiety and so forth), but mainstream computer histories tend to focus on what got made and how it was made rather than exploring dissent.

But if I was partly interested in an absence, I was also intrigued by recurrence. As disenchantment and concern around social media, platforms, and a crisis of epistemic culture rises as a public concern, I am struck by the degree to which we have been here before. We have powerful ways of thinking about robots and AI, about surveillance and capture, about bureaucratic states and computer control and indexical realism more or less ready to hand.

Q. In your view, wherein lies the book’s main contribution to our understanding of technological cultures?

The book re-frames contemporary discussions of disenchantment with technology and with technological cultures by pointing to the degree to which these issues around control and freedom, epistemic shifts, power and the amplification of difference, ‘being human’ or ‘being machine’, are not new at all, nor even exceptional – at least if that suggests we should dis-embed them from earlier histories and from the social and cultural contexts in which they emerge. Establishing this enables the generation of a different way of accounting for current and recurrent panics and anxieties around computation and automation and that’s one contribution. Making these arguments has also necessitated contesting assumptions about the relationship between cultural studies and media archaeology – which are, I argue, not so far apart as some of their proponents would like to suggest.

Q. What would readers be surprised to learn about in your book?

- …perhaps that the first conference on ‘cyberculture’ was held in 1964? Attendees included Hannah Arendt, the philosopher; black activist and auto worker, James Boggs; and the feminist, Betty Friedan.

- At one point there were as many paid-up members of an anti-computing league in England as there were computers.

- F.R. Leavis suggested that the novels of CP Snow, his adversary in the Two Cultures debate, were written by ‘a computer named Charles’.

- Marge Piercy’s feminist SF novel Body of Glass was a direct engagement with masculine cyberpunk and cyberspace – and should be read!

Anti-computing: Dissent and the Machine is part of the OAPEN Library and can be downloaded for free.