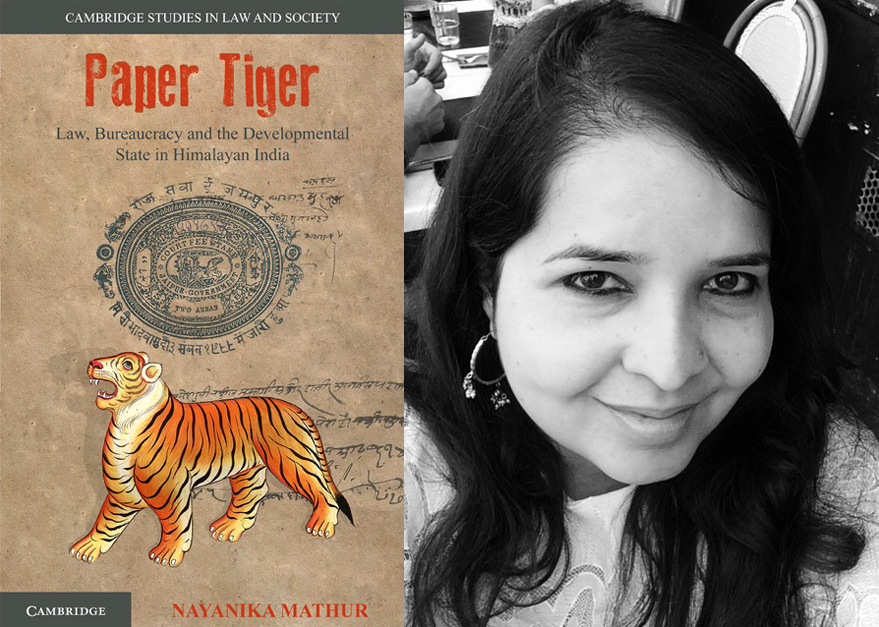

Last year, former CRASSH Research Fellow Nayanika Mathur was awarded the American Ethnological Society’s Sharon Stephens Prize for her monograph, Paper Tiger: Law, Bureaucracy and the Developmental State in Himalayan India. We asked Nayanika, now Associate Professor at Oxford, a few questions about this compelling book.

Q. Nayanika, you are currently Associate Professor in the Anthropology of South Asia at Oxford. What was the subject of your research at CRASSH, and how long were you affiliated to the Centre?

I was a Research Fellow at CRASSH from April 2013 till September 2016 so almost 3.5 years. I worked with the Conspiracy and Democracy project and researched the relationship between the use of new technologies in the working of government and the rise in conspiracy theories/suspicion of democracy in India. I am continuing research on this project though the focus has shifted somewhat to examining the relationship between technocracy, new technologies, and political forms in South Asia. The CRASSH Fellowship also gave me the time and space I so desperately needed to finish my first book, Paper Tiger, which is a revised version of my PhD dissertation and was published in early 2016 by Cambridge University Press.

Q. Congratulations on winning the American Ethnological Society’s Sharon Stephens Prize for Paper Tiger! What is the book about?

Thank you!

Paper Tiger is an ethnographic study of the developmental Indian state with a focus on quotidian bureaucracy. It reads and presents several, much-debated issues – poverty, unemployment, time, space, neoliberalism, welfare, wildlife conservationism – through an ethnography of law and bureaucracy. I think the prize citation by the American Ethnological Society does a better job of describing the book than I do, so here it is in full:

Paper Tiger uses the sensational story of a man-eating big cat on the run to tell a much more subtle story of the everyday life of law and bureaucracy on the Himalayan borderland. It reveals the complexity of bureaucratic practice as it unfolds in its most ordinary everyday embodiment – in the way government officials read and write letters, hold meetings, file, produce and circulate documents, reflect on their official postings, and the spaces officials occupy. The point of it all is to demonstrate the myriad ways in which the state presents itself through and by the laws it intends to implement.

The committee was impressed with the detailed account of paper and its circulation, which works to reveal the unintended consequences of reforms, the problems with implementing new programs and the inability of state officials to act when faced with crises. The book was simply a joy to read: rich, lively, and theoretically compelling. Paper Tiger pushed us to rethink how the state operates in India and beyond.

The committee felt that a major strength of this book was that its theories can and (we believe) will be applied to a vast number of ethnographic contexts. Although it presents a unique explanation for what progressive laws can and cannot do in post-liberal India, the way Mathur theorizes the Indian state’s effort to render itself more transparent and accountable will be helpful to many anthropologists as they wrestle with the double-edged effects of reform in a variety of settings.

In the way Paper Tiger shifts the frames of the debate on state failure and opens up a fresh, new understanding of the workings of the contemporary state governance, we deemed it innovative, theoretically astute, ethnographically rich – and thus an ideal fit for the Sharon Stephens Book Prize.

Q. Who did you have in mind when you wrote the book? Would it make sense to someone outside your field?

My ambition for Paper Tiger when I was writing it was that it be a simple but serious ethnography. I am an avid reader and grew up considering fiction to be the most superior writing form possible. However, more recently I have really fallen in love with ethnography as a genre of writing and hope that Paper Tiger presents an example of what worlds can be revealed through fine-grained ethnographic work.

Some of my own favourite ethnographies remain timeless but also highly accessible to non-anthropologists. I do think Paper Tiger can be read by anyone who is interested in understanding a bit more about the Indian state and how its labyrinthine bureaucracy functions (or not!). I think this book might be of particular interest to those – academics or otherwise – who work on/are interested in development, law, and governance anywhere in the world. I also think this book will be of interest to those who are perplexed by why the Indian state consistently fails in implementing its well-intentioned and otherwise sophisticated plans, policies, and laws.

Q. What do you find particularly interesting about the topic and/or field?

What I find particularly intriguing is how little has been written about bureaucracy, especially how actually-existing-bureaucracies function in the global South. Part of my argument in Paper Tiger is that we need to craft new languages to capture the everyday life of bureaucracy. There is reams of disparaging and normative work on how bureaucracies are stultifying or dehumanising, but we don’t have more detailed and empathetic accounts in the social sciences of bureaucrats as individuals or bureaucracies as particular forms of lived organisations that produce the peculiar results that they do. Fiction writers, such as Kafka, Orwell, and Gogol, are better at capturing the banality and potency of bureaucracy though often at its most dystopian or surreal.

I am currently finishing my second book, Crooked Cats, which describes human-big cat conflict in South Asia. (Once again, much of the fieldwork for this book as well as thinking was undertaken while I was at CRASSH.) In this book too, I find some of the most interesting aspects of the relationship between humans and predatory tigers/leopards/lions to emerge from a closer analysis of how big cats have been historically and currently governed. In other words, to understand why big cats might decide to kill and eat humans I am fascinated by what the details of the processes through which they (the animals) are regulated and managed reveal: their naming, identification, hunting, capturing, breeding, conserving, and trapping.

Q. Where might I find a copy?

You could buy it off either the Cambridge University Press bookshop in the UK or the (much cheaper) South Asian version if in that part of the world. I have been promised the paperback will be out soon!

Q. Please summarise the book in a tweet.

‘The Indian state is nothing but a paper tiger’ is a common complaint, which accurately captures its ineffectuality. Ethnographically, however, ‘paper tiger’ becomes an emic category that opens up a radically new understanding of the failure of the Indian state.