The upcoming conference Objects in Motion emerged from my longtime interests in both interdisciplinarity and material culture. My career trajectory has spanned the hard sciences and archaeology, writing and communicating about those modern subjects and their histories, and now academic history and museums. As a result of this background, interdisciplinarity and material culture were inevitable elements of my own research.

For the past twelve years, I have most often focused on the trade in and many uses of the pervasive early modern technologies known as optical, mathematical and philosophical instruments. It was natural with this topic to delve into the surviving material culture as well as archival manuscripts, and to draw upon the tools and approaches of specializations beyond just history of science. These included the full spectrum of historical and material specialties as well as museum and archival practice, but also subjects such as geography – which introduced me to the useful tool of and theories regarding digital mapping.

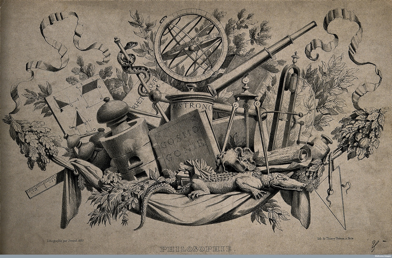

Early 19th-century depiction of optical, mathematical and philosophical instruments among other symbols of ‘philosophy’. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

The theme of Objects in Motion was initially prompted by my research into the difficulties of using early modern instruments in different locations and contexts, begun while participating in research and digitization projects on the British Board of Longitude at Cambridge and continued while at CRASSH. This research set me to thinking about the broader theme of all types of objects in cultural, temporal and geographical transition. This chimed with the ‘material turns’ which have taken place in recent years across a number of academic disciplines as well as with the interests and media of the worlds of art, museums and cultural heritage. The subject is both a central part of the human experience and of the diverse fields which study and interpret it, and a lens through which to better understand and to explore issues and dynamics from ancient to modern times.

I have been overjoyed by the positive response to the conference theme from around the world and across different fields. When going through the difficult process of paring down the proposals to three days’ worth, I aimed for diversity of topics, speakers and methodologies. Despite this diversity, many resonances arose among the paper proposals and my final selections as well. Some were between papers looking at similar topics from different angles: for example John P. McCarthy speaking about historic African American cemeteries and Dana E. Byrd discussing the Civil War plantation piano, or Emma Martin on colonial transformations of Tibetan book covers and Katharina Nordhofen on Byzantine ivories being turned into Ottonian book covers.

13th-century wooden Tibetan book cover at the Walters Art Museum. Credit: Wikimedia.

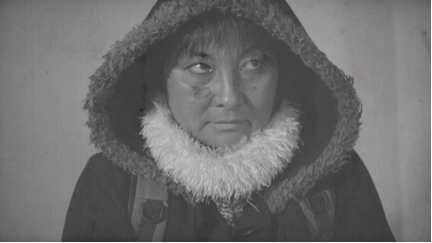

Other resonances reflect trends across material culture studies. Textiles and clothing made a strong showing among both the proposed and selected papers and artwork. This reflects the importance of textiles across cultures in both utilitarian and symbolic senses, as well as how in many cases they tie into the study of the everyday or of women’s work. Over time, textiles and clothing styles can easily adopt changing meanings within the context of cultural heritage and/or politics and nationalism as well. At the conference, Katie Hickerson will be discussing the Mahdist Jibba of Sudan, Stephanie Bunn felt textiles in Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia, and Christina Williamson a century-old Inuit parka.

Another common theme which emerged among proposals and papers was everyday material culture, as in the case of some textiles. In many instances, this theme focused on the transformation from ‘ordinary’ to ‘extraordinary’ through transitions of time, place and/or context. Sometimes the transition occurred through the European ethnographic collection of objects from outside Europe. This is referenced in a number of the conference talks and in the art of Chris McHugh and film by Jade Gibson. In other instances, the everyday became the unique through its survival and reinterpretation over time (as with the ash impression from Pompeii which drives the film La Nuvola e Issìone) or was used as fodder for creating objects of unique importance (as with the everyday objects among John McCarthy’s African American grave goods – so much like early modern tokens).

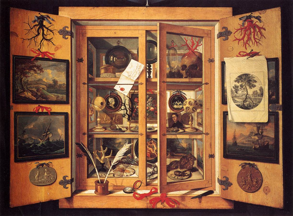

Late 17th-century depiction of a cabinet of curiosities at the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure. Credit: Wikimedia.

Material culture ranges from these most intensely personal of objects to the civic and communal. There are the personal treasures memorialized by Jane Watt’s Cabinet of Curiosities and the characterful family doodles dramatized by Danny Braverman in Wot? No Fish!!. At the other other end of the spectrum, there are objects and entire environments which have broader communal identities and existences as well as a multitude of personal significances and uses.

This encompasses all aspects of the built environment, including its incorporation of objects from other contexts – as with Gabriella Cirucci’s Roman reuse of Greek gravestones, or the adoption of historical and non-European objects and architecture into Tim Knox’s country houses. It also encompasses the diverse material elements which make up entire buildings or cities, and how those assemblages as a whole can transition. Examples include Nazneen Ahmed’s Church of St Thomas the Apostle and Shri Kanaga Thurkkai Amman Hindu Temple in London, and Barbara Garrie and Rosie Ibbotson’s discussion of post-earthquake Christchurch in New Zealand.

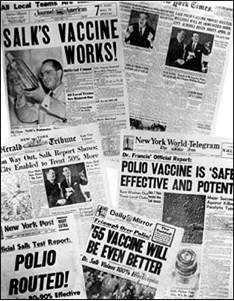

Similarly, there can be collisions between the intended meanings of material culture and its actual uses and interpretations, as it transitions between contexts. This is a frequent element of the material culture of historical and modern science, medicine and technology. Technologies and treatments, plus their associated ideas and techniques, may have been invented with one use or type of performance in mind. However, ‘universality’ is almost always derailed by either the challenges of different cultural and environmental contexts (as with Dora Vargha’s discussion of global polio vaccination) or by individual user applications (as with Claire Sabel’s nineteenth-century ‘colorimeters’).

1955 newspaper headlines about Jonas Salk’s breakthrough in polio vaccination. Credit: Wikipedia.

Objects in Motion encompasses the modern arts as well as these topics in academia, museums and heritage. Art is a key arena for the reinterpretation and transformation of material culture – whether as commentary on objects and collections, in response to associated issues and events, or for the conception of something entirely new. Art can employ and react to objects which belong(ed) to other people, as with the Joseph Cornell dioramas about to go on display in London or with the work of our conference artists. Or it can employ the most personal of belongings, as with Tracey Emin’s best-known installations or Danny Braverman’s incorporation of family drawings into his one-man play.

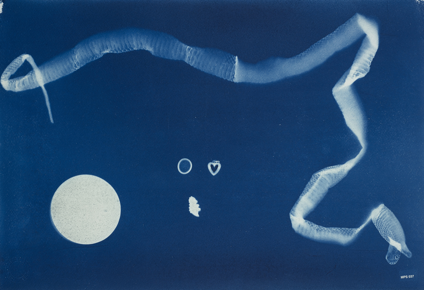

In recognition of art’s frequent contributions to and commentary on material transitions, Objects in Motion will exhibit visual, ceramic and film art and present talks about art and theater. Artist Jane Watt, a Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at University Campus Suffolk, brings her Cabinet of Curiosities project which memorialized Cambridge inhabitants’ valued possessions. The objects were transformed into cyanotypes, which will hang in the Alison Richard Building, and into audio and video recollections which can be viewed in a mobile art studio along with further cyanotypes and a short documentary film.

Credit: Jane Watt

Chris McHugh, Ceramic Artist in Residence at the National Glass Centre at the University of Sunderland, will exhibit his George Brown Series in the Alison Richard Building. These ceramic vessels were a response to the George Brown Collection – more than 3000 ethnographic specimens collected while Brown was a missionary in Oceania between 1860 and 1907 and ‘one of the most mobile collections in the world’ – as well as a response to the material culture of both colonizers and colonized.

Credit: Chris McHugh

Artist/anthropologist Jade Gibson of the Wits City Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa will install her short silent film (in collaboration with cinematographer Gareth Jones) Wish You Were Here in the Alison Richard Building and at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The film draws upon the material culture of early European ethnography but also turns Gibson into an ‘ethnographic art object’ herself, assuming 19th- and early 20th-century imagery in order to explore and explode reactions to her own half-British and half-Filipino ancestry.

Credit: Jade Gibson / Gareth Jones

There will also be a showing of the short documentary film La Nuvola e Issìone – produced by the University of Foggia, directed by Pino Casolaro, and written by Casolaro and Corinna Guerra. Shot on location, the film semi-fictionally explores themes such as love through a now-vanished early modern cast from the ash at Pompeii which became famous across Europe and has been interpreted differently by different authors and eras. Casolaro is an actor, director, and professor of Fine Arts at the University of Foggia while Guerra is an Honorary Fellow in History of Science at the Università degli Studi di Bari.

In addition to these art and film installations, there will be a number of talks at the conference on art. This includes art both historical (as with Elsje van Kessel on temporary exhibitions in early modern Italy) and modern (as with Braverman’s play, and Simon Kaner and Liliana Janik discussing modern artists’ reengagement with ancient Japanese pots).

Convening Objects in Motion has provided an embarrassment of riches about material culture in transition from across the worlds of art, academia and heritage. Fostering dialogue across these diverse arenas will allow us to explore and to learn from our colleagues’ approaches and knowledge sets – in addition to being a fascinating experience.