Text by Expertise Under Pressure‘s co-investigator Dr Emily So assisted by research associate Dr Hannah Baker. Originally published on 4 June 2020 on the Centre for Humanities and Social Change website and re-posted here with kind permission from the author. Since the publication of this post, the UK government’s policy on face coverings has changed.

I was born and raised in Hong Kong. During the Covid-19 pandemic, my friends and family have told me that if you don’t wear a face mask/covering, you are the odd one out. Vending machines selling disposable face masks are common and the government has issued every resident with a reusable face mask. Many countries and cities around the world have followed suit.

There is a rich history of face masks and their origins. In Asian cultures, masks are respected as the social norm. You wear one when you are ill to keep your germs from passing onto others. Yet in the UK, where I now live, donning a face mask attracts public attention in the opposite way, that somehow the wearer has succumbed to fear and is wearing a mask to protect themselves. The debate over in western societies since the pandemic has revolved around the ability of masks to stop transmission of and protect the wearer from potentially viral airborne particles.

By wearing a face mask, are we keeping the germs in or out?

In this short blog, I am not going to embark on a ‘to wear or not to wear’ debate as I have no credentials to argue for either side and will leave Professor Patricia Greenhalgh and Professor Graham Martin to battle it out in the ring. What I am interested in is the timeline of advice on face masks in the UK and what has contributed to its current policy.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic on the 11 March. The first piece of advice I received about face masks from an expert on the BBC was on the 13 March where Dr Shunmay Yang from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine explained if masks really protected people from contracting the virus. Her stance and the one of the UK government at the time was that face masks should be reserved for healthcare workers and those who are already infected. Looking back through the newspaper archives, when interviewed on the BBC the day before, Dr Jenny Harries, deputy chief medical officer, highlighted that risks of catching the infection could be increased due to the incorrect use and disposal of masks and

because of these behavioural issues, people can adversely put themselves at more risk than less.

– Dr Jenny Harries, BBC interview, 12 March 2020.

Tracking the pieces of advice since then from experts such as Dr Yang and the government, based on the science from Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), we found the following:

Mid-March to end of March. Panic buying was rife as rumours spread of an imminent national lockdown. Face masks were on the list of items in high demand and there were reports of opportunists taking advantage of the situation with fake Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and other Covid-19 related supplies. Worried about the scarcity of supplies to key healthcare workers, the Government reiterated their advice to the public and stressed that wearing a face mask is not recommended for people with no symptoms.

The UK was put under a strict lockdown on 23 March.

Early April. Professor Jonathan Van-Tam reiterated at the daily briefing (4 April) that wearing of face masks by healthy people is not recommended by the Government, he goes on to say that while the practice seemed “‘wired into’ some southeast Asian cultures, there was no evidence that general wearing of face masks by the public who are well, affects the spread of the disease in our society” He added: “In terms of the hard evidence and what the UK Government recommends, we do not recommend face masks for general wearing by the public.” Social distancing remained the key mitigation strategy for Covid-19.

Echoing the Government’s messages are those from the WHO and experts from the UK, including Professor Bill Keevil, Professor of Environmental Health at the University of Southampton, who when interviewed by the Evening Standard on 9 April was asked amongst other questions the following two: If I wanted to make my own, would you recommend it? Why are we seeing more people wearing masks? His answers being:

“No. It will not protect you.” (but in answer to the first question, there was no mention of whether it could protect others.)

“The US government is provoking this new interest in face masks because they have knee-jerked. That is because of the concept of symptomless carriers, who have the virus but do not show any signs of it. So what the US government has done is say: ‘People should wear masks.’ But if people are wearing inappropriate face masks, it is creating a false sense of security.”

By Mid-April the mayor of London, Sadiq Kahn, was urging the Government to reconsider their advice on facemasks, he said that wearing non-medical facial masks, such as a bandana, scarf or reusable mask, would add “another layer of protection” to the public. His letter to the Transport Secretary Grant Shapps says he is lobbying for masks to be worn in circumstances where people cannot keep two metres apart, such as on public transport or while shopping. Mr Shapps however said it is “not the right moment” to encourage people to wear masks – adding that the Government needs to look at all the evidence.

21 April. SAGE met to discuss the advice on face masks. The minutes to this meeting were published on the 29 May.

23 April. SAGE submitted their review stating the evidence is weak. At a daily briefing, Dr Jenny Harries, said the fact the issue was being debated means “the evidence either isn’t clear or is weak”.

She was also asked to comment on whether face coverings could have an effect on the London underground, where she said it was possible there could be “a very, very small potential beneficial effect in some enclosed environments” but no reference was given. Professor Martin Marshall, chairman of the Royal College of GPs, also echoed this and told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “there was no research to support wearing a mask if you were fit and well, and there was even a risk of picking up the infection if people were constantly adjusting it and touching their face.” He goes on to say that “I think the guidance that we’re expecting to hear is that the wearing of face masks is a voluntary activity, not mandated, and it certainly makes a lot of sense to focus limited resources that we have at the moment on those who have greatest need and that’s the health professionals.”

28 April. Michael Gove, the Cabinet Office Minister, confirmed that a “domestic effort” has been launched to slow the spread of coronavirus by producing masks that “limit the droplets that each of us might be responsible for”. However, the Health Secretary Matt Hancock said, “On face masks, we are guided by the science and the UK Government position hasn’t changed, not least because the most important thing people can do is the social distancing… as opposed to the weak science on face masks, there is very clear science on social distancing. That is our absolute priority in terms of the message to the public.”

Meanwhile, the First Minister of Scotland says Scots over the age of two should wear a cloth covering, such as a scarf or t-shirt, in “an enclosed space where you will come into contact with multiple people and safe social distancing is difficult – for example on public transport or in shops”. The Scottish Government unveiled its own guidance on this issue, suggesting the voluntary wearing of coverings based on the same evidence and advice from SAGE. Downing Street said the Prime Minister wanted to maintain a UK-wide response to coronavirus as far as possible.

30 April. Boris Johnson is back at Number 10 chairing the press conference following his stay in hospital and Chequers after contracting Covid- 19: “What I think SAGE is saying, and what I certainly agree with, is that as part of coming out of the lockdown, I do think that face coverings will be useful both for epidemiological reasons but also for giving people confidence they can go back to work” the PM said. The term ‘face coverings’ was used at the Downing Street daily briefings for the first time, a term which sets them apart from medical-quality masks.

1 May. Ministers have yet to make a final decision on whether the public will be advised to wear face coverings, but the advice from science suggested that they have a weak but also positive effect in reducing transmission from asymptomatic people where physical distancing was not possible.

4 May. Ministers confirm stockpiling of PPE equipment for healthcare workers and public use.

5 May. A day after PPE was announced, Sir Patrick Vallance told the parliament’s health and social care committee SAGE thinks the evidence on masks preventing the spread of infection from one person to another is “marginal but positive“.

11 May. Two months after WHO declared a global pandemic, the UK public are urged to wear a face covering if social distancing is not possible. The government’s current (May 2020) guidelines include making a face covering out of an old t-shirt to provide some protection for others you come into close contact with.

As I review this timeline, two things struck me. The timing of government advice which has been emphasised as “following the science” and the loose use of the word ‘evidence’. Local Government Minister Simon Clarke told ITV News on the 20 April that the guidance around face masks “remains the same” until a “scientific steer” is given by SAGE. “At the moment this isn’t what is being recommended and therefore it isn’t government policy, we’re prioritising getting material to the frontline. If that advice changes then clearly that is something, we will work to accommodate over the weeks ahead.” Should the two have been linked – the advice on whether face masks become mandatory of the public based on evidence from science and prioritisation of “getting material to the frontline”? Does that imply the “scientific steer” is secondary to how much PPE the country can stockpile?

Given the central role science has taken in this and all other strategic decisions the government has made, it is hard to not feel that the science is politicised and orchestrated at times. To understand why mask guidelines have been so varied, in the US National Public Radio (NPR) reached out to specialists in academia and in government. What they learned was that face mask guidelines are about science – but go beyond. The reasons for a policy may have to do with practical considerations like the national supply of masks but may also reflect cultural values and history. In Eastern Asian countries, the attitude is perhaps one of ‘better safe than sorry’, particularly in countries where they had experienced SARS.

Even though the central arguments and messaging have not changed – not mandatory to wear face masks or coverings in the UK and do not deplete our frontline healthcare workers of PPE, the difficulty in accessing the evidence informing the scientific advice has left me and perhaps many others confused and anxious. In the minutes of the 21 April SAGE meeting it states that evidence (point 10 in the minutes) that exists in marginally positive for the use of masks and RCT (Randomised Clinical Trails) evidence (point 11) is weak and that it would be unreasonable to claim large benefits from wearing a mask. Though evidence was been referred to, these minutes did not form part of the information pack to the public as they were only published on the 29 May.

The Expertise Under Pressure’s ‘Rapid Decisions Under Risk’ case study spun out of frustration and confusion of where my own professional advice was heading in the field of estimating losses due to natural disasters. I was concerned about accountability but more importantly, I was worried about the impact of science-led advice on the public. By allowing the media to pick and choose what to present to the public, since the evidence used by SAGE has not always been made available, any scientific studies are up to public interpretation and can be taken out of context. There are many to choose from. Scientific studies exploring the benefits of face coverings in a pandemic would vary in sample size, context and focus. The phrases ‘randomised trials’, under ‘medical conditions’, ‘community settings’, ‘observational evidence’ comes to mind. As a member of the public, how do I decipher these terms and what do they mean? Am I therefore comparing apples and oranges if I try to contrast the arguments based on studies designed with different parameters?

How does a study make the cut to become evidence examined by SAGE?

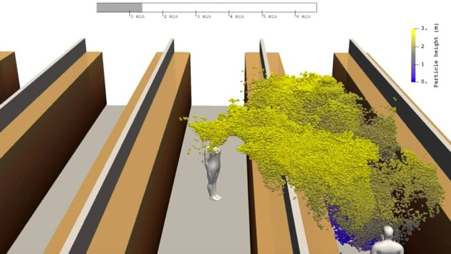

The image below is taken from a study (preprint) carried out by Aalto University, the Finnish Meteorological Institute, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland and the University of Helsinki on a scenario where a person coughs in an aisle between shelves, like those found in supermarkets. This was picked up by most news platforms in the UK, including Sky News and the Daily Mail, and was making its rounds on Twitter and other social media outlets on the 10 April, a month before the official advice on face coverings in public settings was given. Supermarkets in the UK have been urging customers to stay two metres apart while walking down aisles, with long queues seen in car parks around the country as staff limit the number of shoppers entering the store at any given time. However, the finding from this study that “deadly coronavirus droplets can spread across two supermarket aisles and infect shoppers, with the bug hanging in the air for several minutes.” has never been addressed officially.

With reference to this issue on face coverings, what is the difference between weak and marginal but positive evidence, hence tipping the advice to the public from not wearing to wearing face coverings? Was it more than just scientific evidence?

This pandemic will test the role of science and scientists in the management of a national and global challenge. There are growing concerns of the independence of advice and some scientists have broken rank and spoken out about the policies supposedly “following the science“. Given Covid-19 is a new virus and a highly contagious and mutating disease, one can be forgiven for being cautious, and a shifting policy based on changing data is expected. However, the dithering and conflicting (with other countries and even with other nations in the United Kingdom) guidance on face coverings and other issues can only, in my opinion, harm the trust of the public in science and experts, if the cause of the shifts in strategies is not explained. In early May, a survey conducted by the Open Knowledge Foundation found that public trust in science has increased following the pandemic but that transparency is key. They found in the Survation (surveying the nation) poll that people are more likely to listen to expert advice from scientists and researchers, if data is openly available for checking and 97% believe it is important that Covid-19 data is openly available for people to check.

Constructive debate of risks and benefits is essential for any national intervention. We all need to be prepared to modify our views. However, open disputes can lead to public distrust and confusion. We as scientists must think of the common good and duty of care to the audience, even though it is the responsibility of the politicians to make the final decisions. As remarked by Professor Trish Greenhalgh “I conclude by thanking my academic adversaries for the intellectual sparring match, but exhort them to remember our professional accountability to a society in crisis.” The only way to be accountable is to be as transparent as possible, to offer and take time to explain the scientific evidence, the imperfect and ever-changing nature of evidence. Perhaps the way to examine the guidance on “to mask or not” is one of precautionary science rather than absolute.

To conclude, there are three main arguments presented here. The first one is that the question about whether masks protect and who they protect is partly cultural because it relies on assumptions about people’s behaviour. The reticence of UK scientists seems to be driven by their sense of how we as a nation would behave with masks, and they will only consider their health effects after some assurance of compliance. But we have all had to change our behaviours for Covid-19, so why would this be one step too far? The second is that the official advisors are not systematic in the sort of evidence they attend to, in particular they approach the question in an individualist way (will it save me?) instead of a broader communal way (would a community that wears masks be safer?). Lastly, my impression is that the scientific advisors are demanding much too high of a standard of evidence than is warranted by the current situation. The Precautionary Principle seems to argue that masks should be recommended even if the case for adopting them is not 100% watertight. Their cautious approach is also inconsistent since other highly uncertain strategies have been adopted, yet masks remain contentious.

I cannot help but wonder if face coverings would be more common and acceptable if the UK government had made it part of their public health requirement early on. After all, this is a small behavioural change that at a communal level could have an impact on slowing the spread. I for one will be donning a mask to keep my own germs in.

End note (added 18:30 4 June): Since the publication of this blog earlier today it has been announced that face coverings will be mandatory on public transport in England from the 15 June – showing a further development in the UK’s changing policy on this issue.

Disclaimer: Published on 4 June 2020. Every effort has been made to scour through the numerous Government websites and reports, relevant papers and stories from the UK media about face coverings over the past two months by myself and my research associate Dr Hannah Baker. However, the author acknowledges there will be key pieces of information she would have missed. This blogpost is her own personal reflections and hers alone.