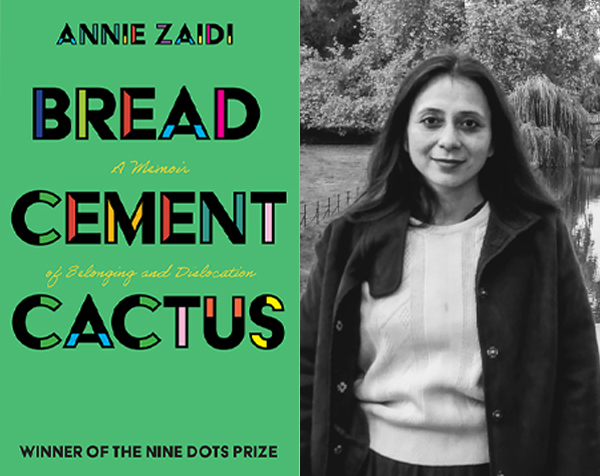

Annie Zaidi, a freelance writer and journalist whose work includes reportage, essays, short stories, poetry and plays, is the winner of the Nine Dots Prize 2019 – 2020. In autumn 2019 she spent some time at CRASSH as a visiting fellow.

Q. Annie Zaidi, what is your book Bread, Cement, Cactus about?

It is a memoir of my attempts at grounding myself in the cultural, political, physical and emotional landscape of my childhood and adult life, up until 2019. The title refers to some of the key aspects of my own story: I spent much of my childhood in an industrial township where cement was manufactured, and in a dry region where cactus grew wild. However, the title is also a reference to the compulsions that drive most people away from the place they have long considered home – bread, of course, but also loosening of bonds between people, and the prickly aspects of a local socio-political climate. Attached to my own memories were several unresolved questions: why did I feel so out of place in the place where I grew up? Who might have felt at home in that place and why didn’t I know what lay beyond the gates of the colony? Is it possible to feel the same attachment to your birthplace if the name of the place is changed? Questions such as these led me to examine my own history against the Partition of India, and social patterns such as marital dislocation, gender inequity, migration patterns in eastern Uttar Pradesh, nativism and a cosmopolitan metropolis like Mumbai, and challenges posed to citizenship.

Q. What drew you to the subject of the Nine Dots Prize question “Is there still no place like home?” and what do you find particularly interesting about it?

Home and belonging have always been of interest to me, perhaps because I found it difficult to define myself clearly without reference to a particular place. Broad-brush identities – religion, nation, ethnicity – were not enough. I noticed too that many other people identify with a micro-geography. They might take the name of a state or a city in relation to themselves but their inner compass was often a particular suburb, or a village. I was interested in what makes people identify with a particular place. More importantly, I was interested in why I was failing to identify myself with similar ease. To understand that, I had to look at my family and how it was different from the majority, how lived experiences determine inner and outer location. Besides that, ‘place’ is central to political discourse. Where you are from is a crucial question, for it is linked to civil and political rights. Wherever you are from is also where you have a right to be.

Q. Around which themes did you decide to structure the book, and to what end?

The book was structured as a series of reflections upon cities or townships with which I have a personal relationship, and the social and political processes that gave shape to these relationships. These are all places in India – Sirohi, Mumbai, Allahabad, Azamgarh-Mau, Lucknow – and I wanted to examine the reasons underlying my attachment to, my identification with, each of these. It was equally important to examine why it was not possible for me to fully belong in a particular place. Sentiments have as much to be with cultural and familial history as they do with historic contestations of power, and my history is linked to the history of the Indian Subcontinent itself. In the course of writing, I also added language and gender as additional ‘locations’ wherein a person can be afforded or denied a feeling of safe refuge, or of being ‘at home’.

Q. In your view, wherein lies the book’s main contribution to our understanding of home and belonging?

In my culture, we are not encouraged to talk about our own contribution to anything (joke). Or, perhaps, not so much of a joke. This word ‘contribution’ has flustered me and it is interesting for that reason, because it brings me back to the question of how to ‘locate’ the self. If the question had been framed as how I have developed my own understanding of home and belonging, I would have described the actual contribution (and my instinct tells me to write ‘attempted contribution’ because that is more culturally correct). To suggest that the book is adding to anybody else’s understanding feels mildly inappropriate. I wonder if it is rooted in a culture where even proud scholars had described themselves as ‘nacheez’, or a non-thing. The assumption was that the person one was talking to was fully aware that one did not, in fact, consider oneself a non-thing and could not be treated as such. To try and answer the question: I believe that emotive subjects such as ‘home’ and belonging, can only be understood as personal narratives located in particular sociological, historical and political frameworks. The book positions ‘home’ as an amorphous, changeable thing as well as an unchanging continuum experienced through language, tradition, memories, sentimental attachments, great and small disruptions of physical boundaries and borders, and contemporary political rhetoric.

Q. What would readers be surprised to learn about in your book?

I myself was somewhat surprised to discover how much of my feelings about ‘home’ had to do with safety, and the right to inhabit and assert one’s own culture, and therefore also how fluid the notion of home is. I had assumed that an individual’s sense of belonging was fairly static and that, even if one’s postal address changed, one’s emotional anchorage would remain attached to roughly the same region. In the course of researching and writing this book, I became aware that home is, in fact, an idea that is subject to constant assessment and negotiation.

- Bread Cement Cactus: A Memoir of Belonging and Dislocation was published by Cambridge University Press in May 2020 and is also available as an Open Access e-book.